Chapter 4: Common Digestive Problems

4.2 Peptic Ulcers

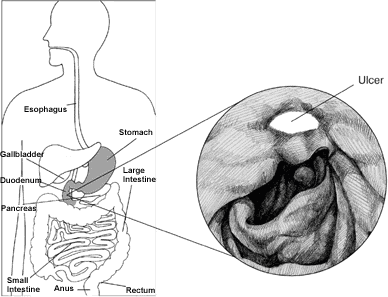

We introduced peptic ulcers briefly in chapter 1. A peptic ulcer (stomach or duodenal) is a break in the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. A peptic ulcer of the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, or duodenal ulcer when located in the duodenum, and esophageal ulcer when in the esophagus. Peptic ulcers occur when the lining of these organs is corroded by the acidic digestive (peptic) juices of the stomach. A peptic ulcer differs from an erosion because it extends deeper into the lining of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum and incites more of an inflammatory reaction from the tissues that are involved. Chronic cases of peptic ulcers are referred to as peptic ulcer disease.[1]

Peptic ulcer disease is common, affecting millions of Americans yearly. Moreover, peptic ulcers are a recurrent problem; even healed ulcers can recur unless treatment is directed at preventing their recurrence. The medical cost of treating peptic ulcer and its complications runs into billions of dollars annually. Recent medical advances have increased our understanding of ulcer formation. Improved and expanded treatment options now are available.

Symptoms of duodenal or stomach ulcer disease vary. Many people with ulcers experience minimal indigestion, abdominal discomfort that occurs after meals, or no discomfort at all. Some complain of upper abdominal burning or hunger pain one to three hours after meals or in the middle of the night. These symptoms are often promptly relieved by food or antacids that neutralize stomach acid. The pain of ulcer disease correlates poorly with the presence or severity of active ulceration. Some individuals have persistent pain even after an ulcer is almost completely healed by medication. Others experience no pain at all. Ulcers often come and go spontaneously without the individual ever knowing that they are present unless a serious complication (like bleeding or perforation) occurs.[2]

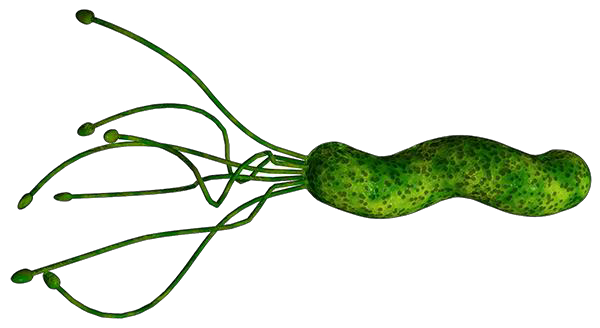

For many years, excess acid was believed to be the only cause of ulcer disease. Accordingly, the emphasis of treatment was on neutralizing and inhibiting the secretion of stomach acid. While acid is still considered necessary for the formation of ulcers and its suppression is still the primary treatment, the two most important initiating causes of ulcers are infection of the stomach by a bacterium named Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications or NSAIDs, including aspirin. Cigarette smoking also is an important cause of ulcers as well as failure of ulcer treatment.[3]

Video Link: Tests for H. pylori (2:05)

Infection with H. pylori is very common, affecting more than a billion people worldwide. It is estimated that half of the United States population older than age 60 has been infected with H. pylori. Infection usually persists for many years, leading to ulcer disease in 10% to 15% of those infected. In the past, H. pylori was found in more than 80% of patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers. Diagnosis and treatment of this infection, the prevalence of infection with H. pylori, and the proportion of ulcers caused by the bacterium has decreased as the causes of peptic ulcers has been identified. It is estimated that currently only 20% of ulcers are associated with the bacterium. While the mechanism by which H. pylori causes ulcers is complex, elimination of the bacterium by antibiotics has clearly been shown to heal ulcers and prevent their recurrence.[4]

NSAIDs are medications used for the treatment of arthritis and other painful inflammatory conditions in the body. Aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), and etodolac (Lodine) are a few examples of this class of medications. NSAIDs cause ulcers by interfering with the production of prostaglandins in the stomach.

Cigarette smoking has been shown to not only cause ulcers, but it also increases the risk of complications from ulcers such as ulcer bleeding, stomach obstruction, and perforation. Cigarette smoking is also a leading cause of failure of treatment for ulcers.

Contrary to popular belief, alcohol, coffee, colas, spicy foods, and caffeine have no proven role in ulcer formation. Similarly, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that life stresses or personality types contribute to ulcer disease.

The goal of ulcer treatment is to relieve pain, heal the ulcer, and prevent complications. The first step in treatment involves the reduction of risk factors (NSAIDs and cigarettes). The next step is medications.

Antacids neutralize existing acid in the stomach. Histamine antagonists (H2 blockers) are drugs designed to block the action of histamine on gastric cells and reduce the production of acid.

While H2 blockers are effective in ulcer healing, they have a limited role in eradicating H. pylori without antibiotics. Therefore, ulcers frequently return when H2 blockers are stopped. Proton- pump inhibitors are more potent than H2 blockers in suppressing acid secretion. The different proton-pump inhibitors are very similar in action and there is no evidence that one is more effective than the other in healing ulcers. While proton-pump inhibitors are comparable to H2 blockers in effectiveness in treating gastric and duodenal ulcers, they are superior to H2 blockers in treating esophageal ulcers.[5]

- https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/peptic-ulcers-stomach-ulcers/definition-facts ↵

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/peptic-ulcer/symptoms-causes/syc-20354223 ↵

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/peptic-ulcer/symptoms-causes/syc-20354223 ↵

- http://www.helico.com/whatishelicobacterpylori.html ↵

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/peptic-ulcer/symptoms-causes/syc-20354223 ↵

Duodenum is the first part of the small intestine.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped bacterium that penetrates the stomach lining , making the tissue more susceptible to the damaging effects of acid, leading to the development of sores and ulcers.

NSAIDs are medications used for the treatment of arthritis and other painful inflammatory conditions in the body. Aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), and etodolac (Lodine) are a few examples of this class of medications.