Chapter 2: Achieving a Healthy Diet

2.7 Discovering Nutrition Facts

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program

The Labels on Your Food

Understanding the significance of dietary guidelines and how to use DRIs in planning your nutrient intakes can make you better equipped to select the right foods the next time you go to the supermarket.

In the United States, the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act passed in 1990 and came into effect in 1994. In Canada, mandatory labeling came into effect in 2005. As a result, all packaged foods sold in the United States and Canada must have nutrition labels that accurately reflect the contents of the food products. There are several mandated nutrients and some optional ones that manufacturers or packagers include.

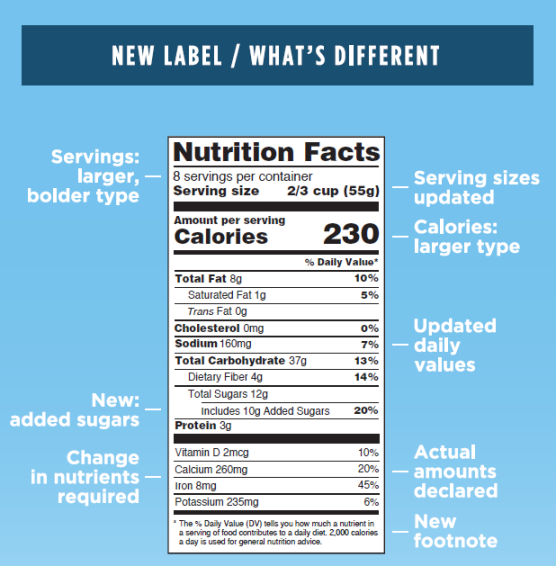

In May, 2016 a new Nutrition Facts label for packaged foods was announced. This label reflects new scientific information and will make it easier for consumers to make informed food choices. Some of the changes made to the label include:

- Increased type size for “Calories,” “servings per container,” and “Serving size”

- Bolded type for the number of calories and the “Serving size”

- Actual amounts of vitamin D, calcium, iron, and potassium (in addition to the Daily Value amounts) are required to be listed. Vitamins A and C are now voluntary.

- Improved footnote to better explain the Daily Value

- “Added sugars” in grams and percent Daily Value are required to be listed due to scientific data the impact of added sugars on caloric intake

- “Total Fat,” “Saturated Fat,” “Trans Fat,” “Cholesterol,” “Total Carbohydrates” are still required on the label

- “Calories from fat” has been removed because the type of fat is important

- Updated values for sodium, dietary fiber, and vitamin D (which are all required on the label) based on newer scientific research

- Updated serving sizes that reflect how much consumers are more likely eating today

- Some packages with serving sizes between one and two are required to be labelled as one serving since most consumers will likely eat it in one sitting

- Dual columns for certain products that are larger than a single serving but could be consumed in one sitting will indicate “per serving” and “per package” amounts

- The compliance date for manufacturers to adopt the new label is July 26, 2018. Manufacturers with less than $10 million in annual food sales will have until 2019.

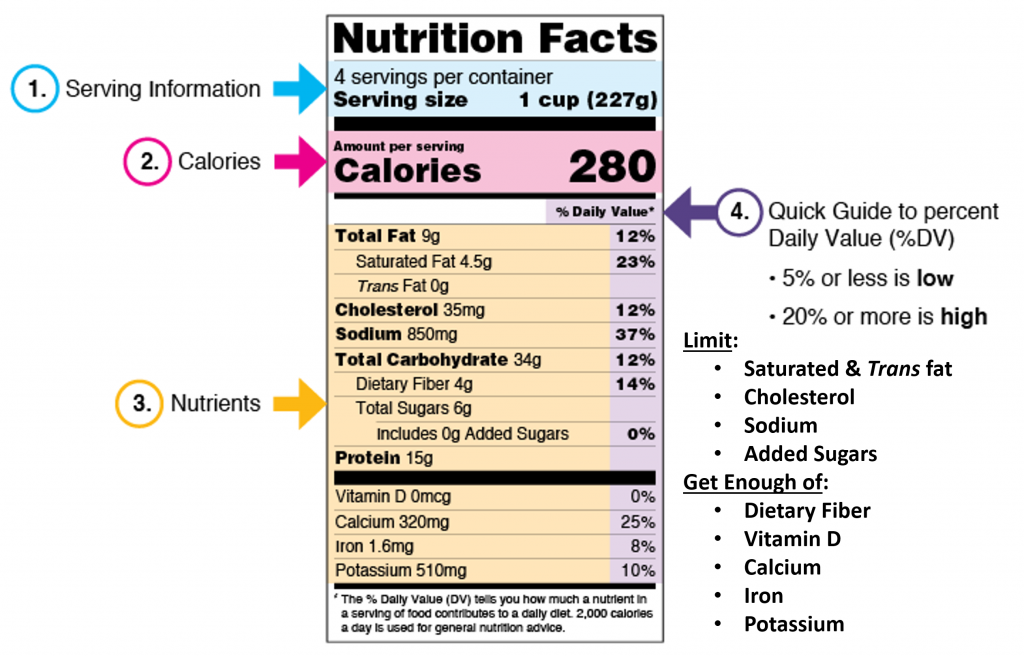

Reading the Label

The first part of the Nutrition Facts panel gives you information on the serving size and how many servings are in the container. For example, a label on a box of crackers might tell you that twenty crackers equals one serving and that the whole box contains 10 servings. All other values listed thereafter, from the calories to the dietary fiber, are based on this one serving, so you need to know how many servings you will be eating. On the panel, the serving size is followed by the number of calories and then a list of selected nutrients. You will also see “% (Percent) Daily Value” on the far right-hand side. This helps you determine if the food is a good source of a particular nutrient or not. The Daily Value (DV) represents the recommended amount of a given nutrient based on the RDI of that nutrient in a 2,000-kilocalorie diet. The percentage of Daily Value (percent DV) represents the proportion of the total daily recommended amount that you will get from one serving of the food. For example, in the food label in Figure 2.71 “Reading the Nutrition Label,” the percent DV of calcium for one serving is 25 percent, which means that one serving of this food (frozen lasagna) provides 25 percent of the daily recommended calcium intake. Since the DV for calcium is 1,300 milligrams, the food producer determined the percent DV for calcium by taking the calcium content in milligrams in each serving, and dividing it by 1,300 milligrams, and then multiplying it by 100 to get it into percentage format. Whether you consume 2,000 calories per day or not you can still use the percent DV as a target reference.

Generally, a percent DV of 5 is considered low and a percent DV of 20 is considered high. This means, as a general rule, for fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, or sodium, look for foods with a low percent DV. Alternatively, when concentrating on essential mineral or vitamin intake, look for a high percent DV. To figure out your fat allowance remaining for the day after consuming one serving of frozen lasagna, look at the percent DV for fat, which is 12 percent, and subtract it from 100 percent. To know this amount in grams of fat, you can look up the recommended daily value of fat in Table 2.71 and multiply the percentage by the maximum amount of fat recommended per day in the Daily Value. Remember, to have a healthy diet the recommendation is to eat less than this amount of fat grams per day, especially if you want to lose weight.

Along with the updated nutrition label, the FDA calculated new Daily Values for many nutrients, based on updated nutrition research. For some nutrients, such as calcium, fiber, and total fat, the recommended amount was increased. For other nutrients, such as sodium and the B vitamins, the recommended daily value was decreased. If you’d like to know more about these changes you can visit the following website: Daily Value on the New Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels.

Table 2.71 Daily Values Based on a Caloric Intake of 2,000 Calories (For Adults and Children Four or More Years of Age), updated[1]

| Food Component | Daily Value (DV) |

| Total Fat | 78 grams (g) |

| Saturated Fat | 20 g |

| Cholesterol | 300 milligrams (mg) |

| Sodium | 2,300 mg |

| Potassium | 4,700 mg |

| Total Carbohydrate | 275 g |

| Dietary Fiber | 28 g |

| Protein | 50 g |

| Vitamin A | 900 micrograms (µg) RAE (retinol activity equivalents) |

| Vitamin C | 90 mg |

| Calcium | 1,300 mg |

| Iron | 18 mg |

| Vitamin D | 20 µg |

| Vitamin E | 15 mg alpha-tocopherol |

| Vitamin K | 120 µg |

| Thiamin | 1.2 mg |

| Riboflavin | 1.3 mg |

| Niacin | 16 mg NE (niacin equivalents) |

| Vitamin B6 | 1.7 mg |

| Folate | 400 µg DFE (dietary folate equivalents) |

| Vitamin B12 | 2.4 µg |

| Biotin | 30 µg |

| Pantothenic acid | 5 mg |

| Phosphorus | 1,250 mg |

| Iodine | 150 µg |

| Magnesium | 420 mg |

| Zinc | 11 mg |

| Selenium | 55 µg |

| Copper | 0.9 mg |

| Manganese | 2.3 mg |

| Chromium | 35 µg |

| Molybdenum | 45 µg |

| Chloride | 2,300 mg |

Of course, this is a lot of information to put on a label and some products are too small to accommodate it all. In the case of small packages, such as small containers of yogurt, candy, or fruit bars, permission has been granted to use an abbreviated version of the Nutrition Facts panel. To learn additional details about all of the information contained within the Nutrition Facts panel, see the following websites:

New Format for Nutrition Facts

The figures below summarize changes to the nutrition label that were finalized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016. As of 2021, all food manufacturers are required to use the new format. The FDA and companies are still working on compliance, so when you’re looking for Nutrition Facts at the grocery store, you may occasionally still see the older version of the label. [2]

There are other types of information that are required by law to appear somewhere on the consumer packaging. They include[3]:

- Name and address of the manufacturer, packager, or distributor

- Statement of identity, what the product actually is

- Net contents of the package: weight, volume, measure, or numerical count

- Ingredients, listed in descending order by weight

The Nutrition Facts panel provides a wealth of information about the nutritional content of the product. The information also allows shoppers to compare products. Because the serving sizes are included on the label, you can see how much of each nutrient is in each serving to make the comparisons. Knowing how to read the label is important because of the way some foods are presented. For example, a bag of peanuts at the grocery store may seem like a healthy snack to eat on the way to class. But have a look at that label. Does it contain one serving, or multiple servings? Unless you are buying the individual serving packages, chances are the bag you picked up is at least eight servings, if not more.

According to the 2010 health and diet survey released by the FDA, 54 percent of first-time buyers of a product will check the food label and will use this information to evaluate fat, calorie, vitamin, and sodium content[4]. The survey also notes that more Americans are using food labels and are showing an increased awareness of the connection between diet and health. Having reliable food labels is a top priority of the FDA, which has a new initiative to prepare guidelines for the food industry to construct “front of package” labeling that will make it even easier for Americans to choose healthy foods. Stay tuned for the newest on food labeling by visiting the FDA website: http://www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/default.htm.

Claims on Labels

In addition to mandating nutrients and ingredients that must appear on food labels, any nutrient content claims must meet certain requirements. For example, a manufacturer cannot claim that a food is fat-free or low-fat if it is not, in reality, fat-free or low-fat. Low-fat indicates that the product has three or fewer grams of fat; low salt indicates there are fewer than 140 milligrams of sodium, and low-cholesterol indicates there are fewer than 20 milligrams of cholesterol and two grams of saturated fat[5]. See Table 2.72 “Common Label Terms Defined” for some examples.

Table 2.72 Common Label Terms Defined[6]

| Term | Explanation |

| Lean | Fewer than a set amount of grams of fat for that particular cut of meat |

| High | Contains more than 20% of the nutrient’s DV |

| Good source | Contains 10 to 19% of nutrient’s DV |

| Light/lite | Contains ⅓ fewer calories or 50% less fat; if more than half of calories come from fat, then fat content must be reduced by 50% or more |

| Organic | Contains 95% organic ingredients |

Health Claims

Often we hear news of a particular nutrient or food product that contributes to our health or may prevent disease. A health claim is a statement that links a particular food with a reduced risk of developing disease. As such, health claims such as “reduces heart disease,” must be evaluated by the FDA before it may appear on packaging. Prior to the passage of the NLEA products that made such claims were categorized as drugs and not food. All health claims must be substantiated by scientific evidence in order for it to be approved and put on a food label. To avoid having companies making false claims, laws also regulate how health claims are presented on food packaging. In addition to the claim being backed up by scientific evidence, it may never claim to cure or treat the disease. For a detailed list of approved health claims, and to learn more about this process, visit the websites below:

Qualified Health Claims

While health claims must be backed up by hard scientific evidence, qualified health claims have supportive evidence, which is not as definitive as with health claims. The evidence may suggest that the food or nutrient is beneficial. Wording for this type of claim may look like this: “Consuming EPA and DHA combined may help lower blood pressure in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension. However, FDA has concluded that the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive. One serving of [name of food] provides [X] grams of EPA and DHA.[7]

Structure/Function Claims

Some companies claim that certain foods and nutrients have benefits for health even though no scientific evidence exists. In these cases, food labels are permitted to claim that you may benefit from the food because it may boost your immune system, for example. There may not be claims of diagnosis, cures, treatment, or disease prevention, and there must be a disclaimer that the FDA has not evaluated the claim[8].

Allergy Warnings

Food manufacturers are required by the FDA to list on their packages if the product contains any of the eight most common ingredients that cause food allergies. These eight common allergens are as follows: milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, and wheat. (More information on these allergens will be discussed in Chapter 9 “Energy Balance and Body Weight”.) The FDA does not require warnings that cross contamination may occur during packaging, however most manufacturers include this advisory as a courtesy. For instance, you may notice a label that states, “This product is manufactured in a factory that also processes peanuts.” If you have food allergies, it is best to avoid products that may have been contaminated with the allergen.

- Source: FDA, https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/daily-value-new-nutrition-and-supplement-facts-labels ↵

- https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm385663.htm ↵

- Food Labeling. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm385663.htm#highlights. Updated November 11, 2017. Accessed November 22, 2017. ↵

- Consumer Research on Labeling, Nutrition, Diet and Health. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/foodscienceresearch/consumerbehaviorresearch/ucm275987.htm.Updated November 17, 2017. ↵

- Nutrient Content Claims. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/ingredientspackaginglabeling/labelingnutrition/ucm2006880.htm. [inactive]Updated December 9, 2014. Accessed December 10, 2017. ↵

- Source: Food Labeling Guide. US Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov. Updated February 10, 2012. Accessed November 28, 2017. ↵

- FDA Announces New Qualified Health Claims for EPA and DHA Omega-3 Consumption and the Risk of Hypertension and Coronary Heart Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-announces-new-qualified-health-claims-epa-and-dha-omega-3-consumption-and-risk-hypertension-and. Published June 19, 2019. Accessed August 31, 2020. ↵

- Claims That Can Be Made for Conventional Foods and Dietary Supplements. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/label-claims-conventional-foods-and-dietary-supplements. Updated September 2003. Accessed November 28,2017. ↵

The Daily Value (DV) represents the recommended amount of a given nutrient based on the RDI of that nutrient in a 2,000-kilocalorie diet. The percentage of Daily Value (percent DV) represents the proportion of the total daily recommended amount that you will get from one serving of the food.

Hypertension is the scientific term for high blood pressure and defined as a sustained blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or greater. Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and reducing blood pressure has been found to decrease the risk of dying from a heart attack or stroke.

Structure/function claims are marketing claims on food or supplement labels that are not supported by scientific evidence. Such claims must not mention cure or treatment of a specific disease and must include a disclaimer that the claim has not been evaluated by the FDA.

An allergy occurs when a protein in food triggers an immune response, which results in the release of antibodies, histamine, and other defenders that attack foreign bodies. Possible symptoms include itchy skin, hives, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and nausea.