Chapter 3: Nutrients in the Body

3.4 Stomach

After going through the lower esophageal sphincter, food enters the stomach. Our stomach is involved in both chemical and mechanical digestion. Mechanical digestion occurs as the stomach churns and grinds food into a semisolid substance called chyme (partially digested food).

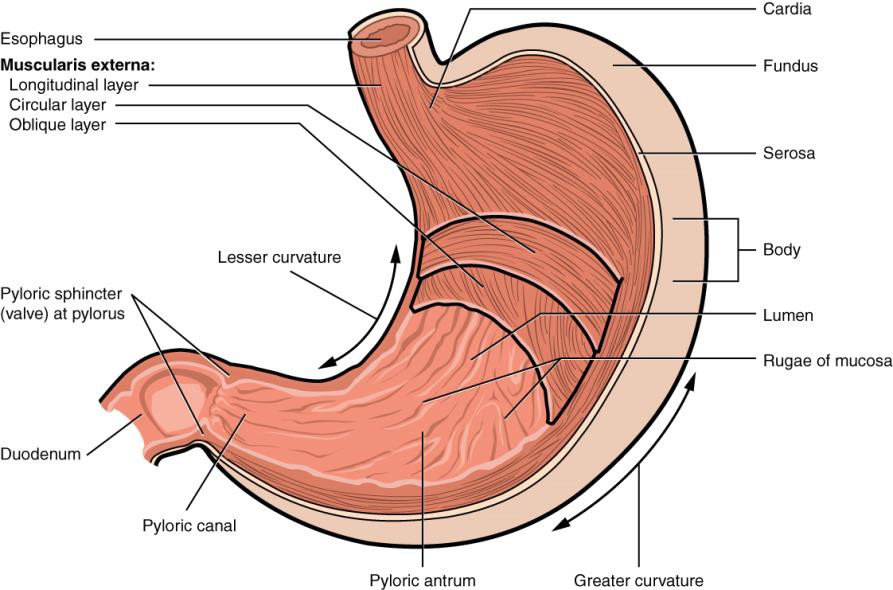

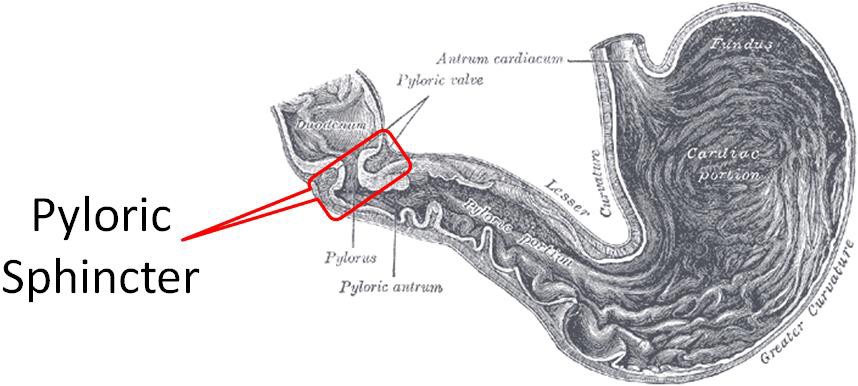

There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus (see Figure 3.41 below). The cardia (or cardiac region) is the point where the esophagus connects to the stomach and through which food passes into the stomach. Located inferior to the diaphragm, above and to the left of the cardia, is the dome-shaped fundus. Below the fundus is the body, the main part of the stomach. The funnel-shaped pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum. The wider end of the funnel, the pyloric antrum, connects to the body of the stomach. The narrower end is called the pyloric canal, which connects to the duodenum. The smooth muscle pyloric sphincter is located at this latter point of connection and controls stomach emptying. In the absence of food, the stomach deflates inward, and its mucosa and submucosa fall into a large fold called a rugae[1]. These rugae increase the surface area inside the stomach, which aids the digestive process.

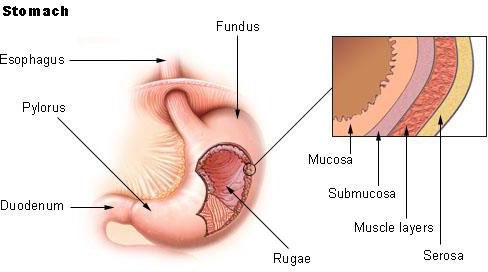

The lining of the stomach is made up of four different layers of tissue. For the purposes of this discussion, we will focus on only the innermost layer. The mucosa is the innermost layer of the stomach (closest to stomach cavity) as shown in the figure below.

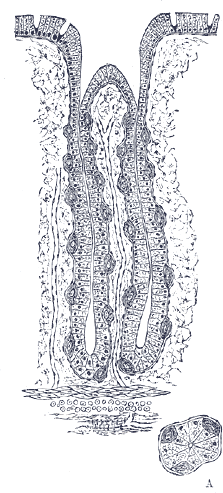

The mucosa is not a flat surface. Instead, its surface is lined by gastric pits, as shown in Figure 3.43 below.

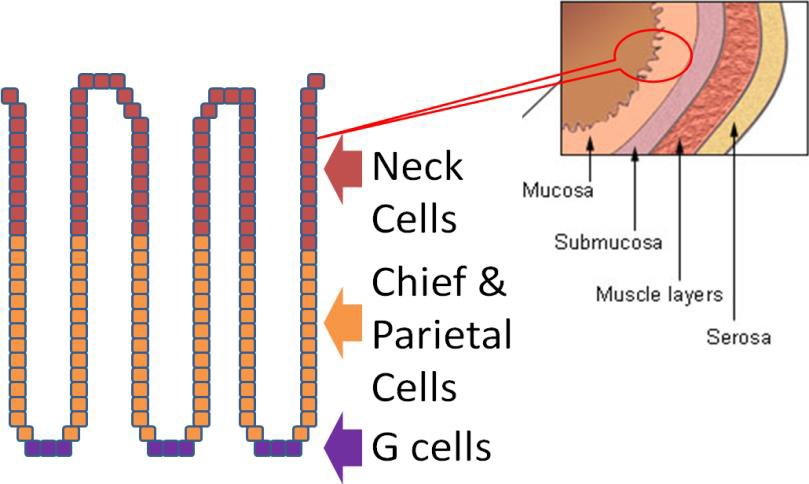

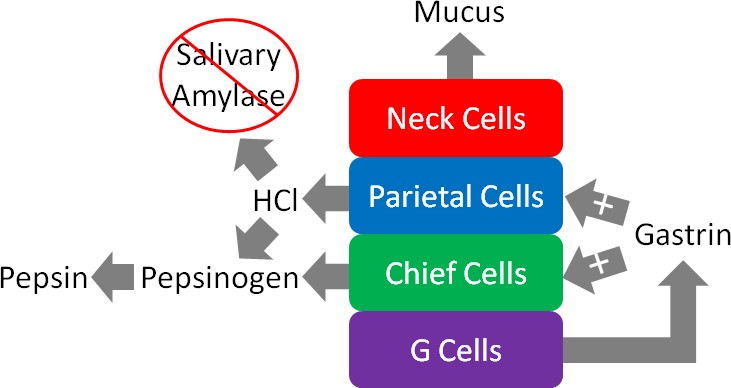

Gastric pits are indentations in the stomach’s surface that are lined by four different types of cells (see Figure 3.44 for names and locations).

The following video is a nice introduction to gastric pits and talks about chief and parietal cells that are covered in more detail below.

Video: Gastric Pits (0:56)

At the bottom of the gastric pit are the gastric enteroendocrine cells (G cells) that secrete the hormone gastrin. Gastrin stimulates the parietal and chief cells that are found above the G cells. The chief cells secrete the pepsinogen. Pepsinogen is the inactive precursor that must be altered to form the active enzyme, pepsin. The parietal cells secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl), which lowers the pH of the gastric juice (water + enzymes + acid). The HCl also inactivates salivary amylase and catalyzes the conversion of the inactive pepsinogen to its active form, known as pepsin. Finally, at the top of the pits are the neck cells (specialized goblet cells) that secrete mucus to prevent the gastric juice from digesting or damaging the stomach mucosa[2]. The table below summarizes the actions of the different cells in the gastric pits.

Table 3.41 Cells involved in the digestive processes in the stomach

|

Type of Cell |

Secrete |

|

Neck (Goblet) |

Mucus |

|

Chief |

Pepsinogen |

|

Parietal |

HCl (hydrochloric acid) |

|

G cells |

Gastrin |

The figure below shows the action of all these different secretions in the stomach.

To reiterate, the figure above illustrates that the neck cells of the gastric pits secrete mucus to protect the mucosa of the stomach from essentially digesting itself. Gastrin from the G cells stimulates the parietal and chief cells to secrete HCl and enzymes, respectively.

The HCl in the stomach denatures salivary amylase and other proteins by breaking down the structure and, thus, the function of it. HCl also converts pepsinogen to the active enzyme pepsin. Pepsin is a protease, meaning that it cleaves the peptide bonds in proteins. It breaks down the proteins in food into individual peptides (shorter segments of amino acids).

The chyme will then leave the stomach in small amounts and enter the small intestine via the pyloric sphincter (shown below). Full emptying of the stomach takes about 2-4 hours.

Table 3.42 Summary of chemical digestion in the stomach

|

Chemical or Enzyme |

Action |

|

Gastrin |

Stimulates chief cells to release pepsinogen Stimulates parietal cells to release HCl |

|

HCl |

Denatures salivary amylase Denatures proteins Facilitates the conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin |

|

Pepsin |

Cleaves proteins to peptides |

- OpenStax, Anatomy & Physiology. OpenStax CNX. Aug 1, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@8.108 ↵

- Gropper SS, Smith JL, Groff JL. (2008) Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing ↵

Sphincters are muscular openings that separate one compartment of the digestive tract from the next.

Gastric pits are indentations in the stomach’s surface that contain hormone- and enzyme-producing cells of the stomach.

A hormone is a compound that is produced in one tissue, released into circulation, then has an effect on a different organ.

Pepsin is a digestive enzyme in the stomach that breaks down the proteins in food into individual peptides (shorter chains of amino acids).

Peptide bonds are bonds formed between the carboxylic acid group of one amino acid and the amino group of another.

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, simple subunits composed of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen.