Chapter 13: Water and Electrolytes

13.9 Hypertension, Salt-Sensitivity, & the DASH Diet

Hypertension

Blood pressure is the force of moving blood against arterial walls. It is reported as the systolic pressure over the diastolic pressure, which is the greatest and least pressure on an artery that occurs with each heartbeat. The force of blood against an artery is measured with a device called a sphygmomanometer. The results are recorded in millimeters of mercury, or mmHg. A desirable blood pressure ranges between 90/60 and 120/80 mmHg. Hypertension is the scientific term for high blood pressure and defined as a sustained blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or greater. Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and reducing blood pressure has been found to decrease the risk of dying from a heart attack or stroke. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2007–2008 approximately 33 percent of Americans were hypertensive.[1]The percentage of people with hypertension increases to over 60 percent in people over the age of sixty.

Approximately 27% of American adults have hypertension (high blood pressure), which increases their risk of developing cardiovascular disease.[2]

There has been much debate about the role sodium plays in hypertension. In the latter 1980s and early 1990s the largest epidemiological study evaluating the relationship of dietary sodium intake with blood pressure, called INTERSALT, was completed and then went through further analyses.[3][4]

More than ten thousand men and women from thirty-two countries participated in the study. The study concluded that a higher sodium intake is linked to an increase in blood pressure. A more recent study, involving over twelve thousand US citizens, concluded that a higher sodium-to-potassium intake is linked to higher cardiovascular mortality and all-causes mortality.[5]

While some other large studies have demonstrated little or no significant relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure, the weight of scientific evidence demonstrating low-sodium diets as effective preventative and treatment measures against hypertension led the US government to pass a focus on salt within the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008. A part of this act tasked the CDC, under guidance from the National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine), to make recommendations for Americans to reduce dietary sodium intake. This task is ongoing and involves “studying government approaches (regulatory and legislative actions), food supply approaches (new product development, food reformulation), and information/education strategies for the public and professionals.”[6]

Salt-Sensitivity

High dietary intake of sodium is one risk factor for hypertension and contributes to high blood pressure in many people. However, studies have shown that not everyone’s blood pressure is affected by lowering sodium intake. Salt-sensitive means that a person’s blood pressure increases with increased salt intake and decreases with decreased salt intake. Approximately 25% of normotensive (normal blood pressure) individuals and 50% of hypertensive individuals are salt-sensitive.[7] Most others are salt-insensitive, and in a small portion of individuals, low salt consumption actually increases blood pressure.[8] Unfortunately, there isn’t a clinical method to determine whether a person is salt-sensitive. There are some known characteristics that increase the likelihood of an individual being salt-sensitive. They are:[9]

- Elderly

- Female

- African-American

- Hypertensive

- Diabetic

- Chronic Kidney Disease

There is some evidence now suggesting that there may be negative effects in some people who restrict their sodium intakes to the levels recommended by some organizations. The second link describes a couple of studies that had conflicting outcomes as it relates to the importance of salt reduction in decreasing blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. The third link is to a study that found that higher potassium consumption, not lower sodium consumption, was associated with decreased blood pressure in adolescent teenage girls.

Web Links:

Report Questions Reducing Salt Intake Too Dramatically

The DASH Diet

To combat hypertension, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet was developed. The DASH diet is an eating plan that is low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and total fat. Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods, whole-grain foods, fish, poultry, and nuts are emphasized while red meats, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages are mostly avoided. In a clinical trial, people on the low-sodium (1500 milligrams per day) DASH diet had mean systolic blood pressures that were 7.1 mmHg lower than people without hypertension not on the DASH diet. The effect on blood pressure was greatest in participants with hypertension at the beginning of the study who followed the DASH diet. Their systolic blood pressures were, on average, 11.5 mmHg lower than participants with hypertension on the control diet.[10]

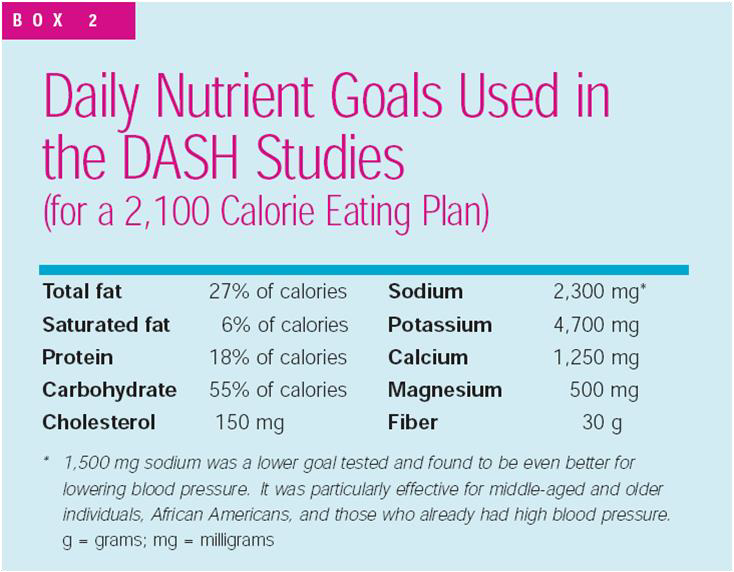

Following the DASH diet not only reduces sodium intake, but also increases potassium, calcium, and magnesium intake. All of these electrolytes have a positive effect on blood pressure, although the mechanisms by which they reduce blood pressure are largely unknown.

The daily goals for the DASH diet are shown in the figure below.

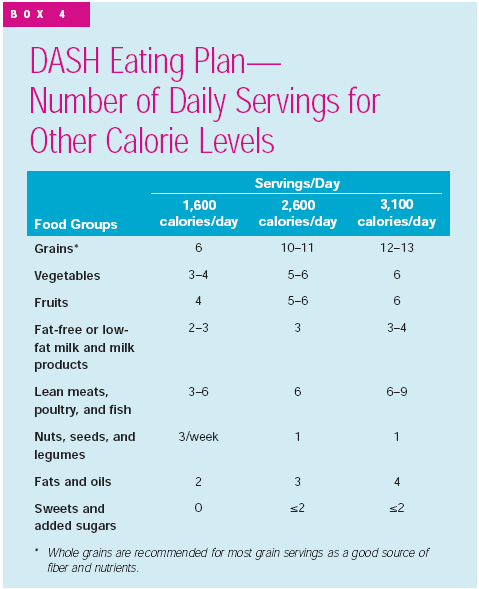

To get an idea of what types of foods and how much would be consumed in the diet, an eating plan is shown below.

The DASH diet has been shown to be remarkably effective in decreasing blood pressure in those with hypertension. Nevertheless, most people with hypertension aren’t following the DASH diet. In fact, evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that significantly fewer hypertensive individuals were following the DASH diet in 1999-2004 than during 1988-1994.[11]

For more information on the DASH diet, see the fact sheet prepared by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the web link below:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “FastStats—Hypertension.” Accessed October 2, 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hypertension.htm. ↵

- McGuire M, Beerman KA. (2011) Nutritional sciences: From fundamentals to food. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ↵

- Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: An International Study of Electrolyte Excretion and Blood Pressure. Results for 24 Hour Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion. BMJ. 1988; 297(6644), 319–28. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1834069/. Accessed September 20, 2017. ↵

- Elliott P, Stamler J, et al. Intersalt Revisited: Further Analyses of 24 Hour Sodium Excretion and Blood Pressure within and across Populations. BMJ. 1996; 312(7041), 1249–53. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8634612. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Yang Q, Liu T, et al. Sodium and Potassium Intake and Mortality among US Adults: Prospective Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171(13), 1183–91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21747015. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Henney JE, Taylor CL, Boon CS. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States, by Committee on Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake, Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12818&page= 19#p2001bcf59960019001. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Whitney E, Rolfes SR. (2011) Understanding nutrition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ↵

- McGuire and Beerman (2011) ↵

- McGuire and Beerman (2011) ↵

- Sacks, FM, Svetkey LP, et al. Effects on Blood Pressure of Reduced Dietary Sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344(1), 3–10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11136953. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Mellen P, Gao S, Vitolins M, Goff D. (2008) Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med 168(3): 308-314. ↵

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are the government agency tasked with monitoring illness in the United States. They gather data from public health departments in all 50 states and monitor the data to detect new outbreaks of disease, monitor existing health concerns, and track the success of public health initiatives. The CDC also carries out research and trains public health experts who can be dispatched to control outbreaks of disease. Much of the CDC’s work is focused on infectious disease, but they also track cases of foodborne illness.https://www.cdc.gov/

The CDC defines epidemiological studies as scientific investigations that define frequency, distribution, and patterns of health events in a population. These studies describe the occurrence and patterns of health events over time.