Chapter 1: Nutrition and You

1.0 Introduction

As we get started on our journey into the world of health and nutrition, our first focus will be to demonstrate that nutritional science is an evolving field of study, continually being updated and supported by research, studies, and trials.

Let’s begin with a story: the story of peptic ulcers and H. pylori.

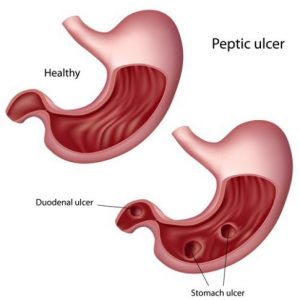

Peptic ulcers are painful sores in the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms of peptic ulcers include abdominal pain, nausea, loss of appetite, and weight loss. The cure for this ailment took some time for scientists to figure out. If your grandfather complained to his doctor of symptoms of peptic ulcer, he was probably told to avoid spicy foods, alcohol, and coffee, and to manage his stress. In the early twentieth century, the medical community thought peptic ulcers were caused by what you ate and drank, and by stress.

In 1915, Dr. Bertram W. Sippy devised the “Sippy diet” for treating peptic ulcers. Dr. Sippy advised patients to drink small amounts of cream and milk every hour in order to neutralize stomach acid. Ultimately, the Sippy diet did not cure peptic ulcers and in the latter 1960s, scientists discovered the diet was associated with a significant increase in heart disease due to its high saturated fat content.

In the 1980s, Australian physicians Barry Marshall and Robin Warren proposed a radical hypothesis — that the cause of ulcers was bacteria that could survive in the acidic environment of the stomach and small intestine.[1] They met with significant opposition to their hypothesis but they persisted with their research. Their research led to an understanding that the spiral shape of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) allows it to penetrate the stomach’s mucous lining, where it secretes an enzyme that generates substances to neutralize the stomach’s acidity. This weakens the stomach’s protective mucous, making the tissue more susceptible to the damaging effects of acid, leading to the development of sores and ulcers. H. pylori also prompt the stomach to produce even more acid, further damaging the stomach lining.

In 1994, the National Institutes of Health held a conference on the cause of peptic ulcers. There was scientific consensus that H. pylori cause most peptic ulcers and that patients should be treated with antibiotics.

In 1996, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first antibiotic that could be used to treat patients with peptic ulcers. Nevertheless, the link between H. pylori and peptic ulcers was not sufficiently communicated to health-care providers. In fact, 75 percent of patients with peptic ulcers in the late 1990s were still being prescribed antacid medications and advised to change their diet and reduce their stress.

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), alongside other public health organizations, began an intensive educational campaign to convince the public and health-care providers that peptic ulcers are a curable condition requiring treatment with antibiotics. Today, if you go to your primary physician you will be given the option of taking an antibiotic to eradicate H. pylori from your gut.

The H. pylori discovery was made recently, overturning a theory applied in our own time. The demystification of disease requires the continuous forward march of science, overturning old, traditional theories and discovering new, more effective ways to treat disease and promote health. In 2005, Marshall and Warren were awarded the prestigious Nobel Prize in medicine for their discovery that many stomach ulcers are caused by H. pylori.

A primary goal of this text is to provide you with information backed by nutritional science, and with a variety of resources that use scientific evidence to optimize health and prevent disease. In this chapter, you will see that there are many conditions and deadly diseases that can be prevented by good nutrition. You will also discover the many other determinants of health and disease, how the powerful tool of scientific investigation is used to design dietary guidelines, and recommendations that will promote health and prevent disease.

“The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’ but ‘That’s funny…’”

– Isaac Asimov (January 2, 1920–April 6, 1992)

- Marshall and Warren. “Ulcers — The Culprit Is H. Pylori!” National Institutes of Health, Office of Science Education. Accessed on November 10, 2011. http://science.education.nih.gov/home2.nsf/Educational+ResourcesResource+FormatsOnline+Resources+High+School/928BAB9A176A71B585256CCD00634489 [inactive] ↵

Nutrition is the sum of all processes involved in how organisms obtain nutrients, metabolize them, and use them to support all of life’s processes.

Nutritional science is the investigation of how an organism is nourished, and incorporates the study of how nourishment affects personal health, population health, and planetary health.

Peptic ulcers are painful sores in the gastrointestinal tract caused by breakdown of the lining of the digestive tract.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped bacterium that penetrates the stomach lining , making the tissue more susceptible to the damaging effects of acid, leading to the development of sores and ulcers.

“heart disease” refers to several types of heart conditions. The most common type is coronary artery disease, which can cause a heart attack. Other kinds of heart disease may involve the valves in the heart, or the heart may not pump well and cause heart failure.

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions in the body and are involved in all aspects of body functions from producing energy, to digesting nutrients, to building macromolecules.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 gives the FDA authority over food ingredients. The FDA enforces the safety of domestic and imported foods. It also monitors supplements, food labels, claims that corporations make about the benefits of products, and pharmaceutical drugs. Sometimes, the FDA must recall contaminated foods and remove them from the market to protect public health.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are the government agency tasked with monitoring illness in the United States. They gather data from public health departments in all 50 states and monitor the data to detect new outbreaks of disease, monitor existing health concerns, and track the success of public health initiatives. The CDC also carries out research and trains public health experts who can be dispatched to control outbreaks of disease. Much of the CDC’s work is focused on infectious disease, but they also track cases of foodborne illness.https://www.cdc.gov/