Chapter 4: Common Digestive Problems

4.1 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

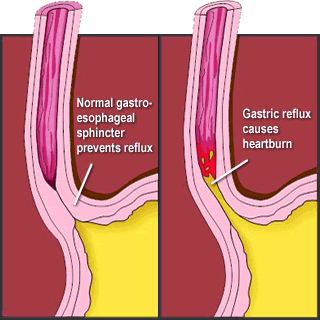

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a persistent form of acid reflux that occurs more than twice per week. Acid reflux occurs when the lower gastroesophageal sphincter (LES) fails to prevent the acidic contents of the stomach from leaking backward into the esophagus and causing irritation.

It is estimated that GERD affects 25 to 35 percent of the US population. An analysis of several studies published in the August 2005 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine concludes that GERD is much more prevalent in people who are obese[1]. While the links between obesity and GERD are not completely understood, the links likely include: a) excess body fat putting pressure on the stomach, b) overeating leading to high pressure inside the stomach, and/or c) increased consumption of fatty foods triggering GERD symptoms.

There are other causative factors of GERD as well. Sometimes the peristaltic contractions of the esophagus are sluggish and can compromise the clearance of acidic contents. In addition, some people with GERD are sensitive to particular foods—chocolate, garlic, spicy foods, fried foods, and tomato-based foods—which worsen symptoms. Drinks containing alcohol or caffeine may also worsen GERD symptoms.

GERD is diagnosed most often by a history of recurring symptoms. The most common symptom of GERD is heartburn but people with GERD may also experience regurgitation (flow of the stomach’s acidic contents into the mouth), frequent coughing, nausea, wheezing, and trouble swallowing. A more proper diagnosis can be made when a doctor inserts a small device into the lower esophagus that measures the acidity of the contents during one’s daily activities.

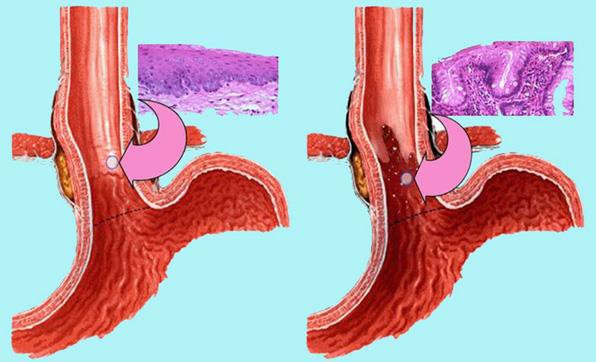

Sometimes a doctor may use an endoscope, which is a long tube with a camera at the end, to view the tissue in the esophagus. About 50% of people with GERD have inflamed tissues in the esophagus. Recurrent tissue damage can cause Barrett’s esophagus[2]. Barrett’s esophagus occurs in 5 to 15 percent of patients diagnosed with GERD and in some of these individuals, the condition may develop into cancer of the esophagus, a highly lethal cancer.

Approximately 35% of children born in the United States have GERD. In babies, the symptoms are more difficult to distinguish from what babies do normally. The symptoms are spitting up more than normal, incessant crying, refusal to eat, burping, and coughing. Most babies outgrow GERD before their first birthday but a small percentage do not.

The first approach to GERD treatment is dietary and lifestyle modifications. Suggestions are to reduce weight if you are overweight or obese, avoid foods that worsen GERD symptoms, eat smaller meals, stop smoking, and remain upright for at least three hours after a meal. There is some evidence that sleeping on a bed with the head raised at least six inches helps lessen the symptoms of GERD. People with GERD may not take in the nutrients they need because of the pain and discomfort associated with eating. As a result, GERD can cause an unbalanced diet and its symptoms can lead to a worsening of nutrient inadequacy, a vicious cycle that further compromises health. Many medications are available to treat GERD, including antacids (Maalox or Mylanta), histamine[3] (H2) blockers (Tagamet, Zantac, Axid, and Pepcid), and proton-pump inhibitors (Prilosec, Prevacid, Nexium, and Aciphex. Evidence from several scientific studies indicates that medications used to treat GERD may accentuate certain nutrient deficiencies, namely zinc and magnesium[4]. When these treatment approaches do not work surgery is an option. The most common surgical treatment involves reinforcing the lower esophageal sphincter, which serves as the barrier between the stomach and esophagus.

The following videos do a nice job of describing the causes, symptoms, and treatments of GERD.

- Hampel, H. MD, PhD, N. S. Abraham, MD, MSc(Epi) and H. B. El-Serag, MD, MPH. “Meta- Analysis: Obesity and the Risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications.” Ann Intern Med 143, no. 3 (2005): 199–211. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16061918 ↵

- https://refluxcentar.com/en/diseases/barretts-esophagus/ ↵

- Hampel, H. MD, PhD, N. S. Abraham, MD, MSc(Epi) and H. B. El-Serag, MD, MPH. “Meta- Analysis: Obesity and the Risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications.” Ann Intern Med 143, no. 3 (2005): 199–211. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16061918 ↵

- Heidelbaugh, J. J. (2013). Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 4(3), 125–133. http://doi.org/10.1177/2042098613482484 ↵

Sphincters are muscular openings that separate one compartment of the digestive tract from the next.

Tissues are groups of cells that share a common structure and function and work together.

Barrett’s esophagus occurs when the linings of the esophagus transform to tissue types that are more consistent with the linings of the stomach or intestine.