6 The Rogerian Argument Model

The Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian argument, inspired by the influential psychologist Carl Rogers, aims to find compromise or common ground about an issue. If, as stated in the beginning of the chapter, academic or rhetorical argument is not merely a two-sided debate that seeks a winner and a loser, the Rogerian argument model provides a structured way to move beyond the win-lose mindset. Indeed, the Rogerian model can be employed to deal effectively with controversial arguments that have been reduced to two opposing points of view by forcing the writer to confront opposing ideas and then work towards a common understanding with those who might disagree.

Figure 6.1 “Carl Ransom Rogers”

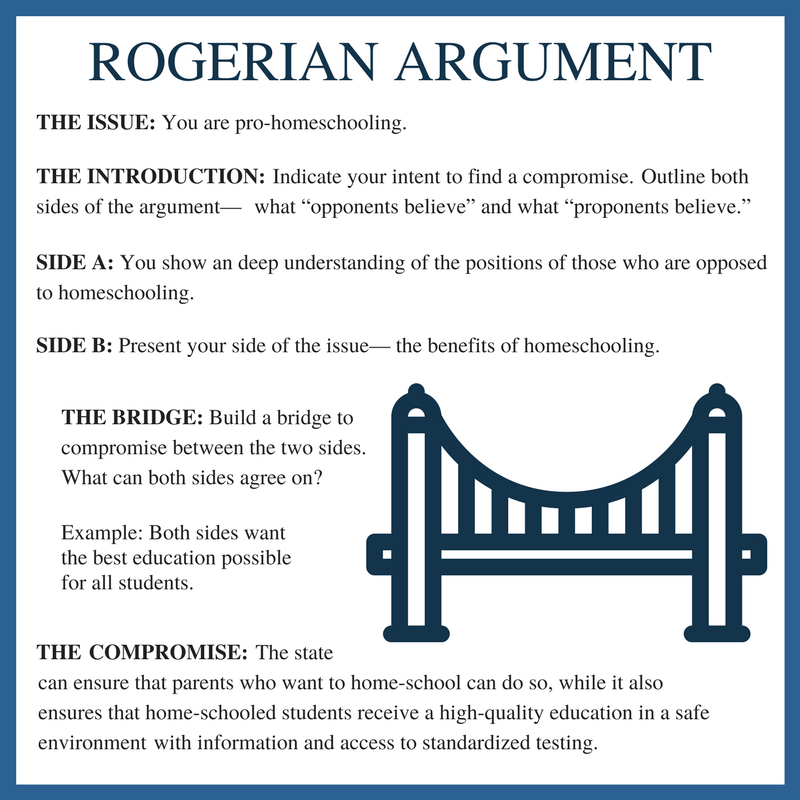

The following are the basic parts of a Rogerian Argument:

1. Introduction: Introduce the issue under scrutiny in a non-confrontational way. Be sure to outline the main sides in the debate. Though there are always more than two sides to a debate, Rogerian arguments put two in stark opposition to one another. Crucially, be sure to indicate the overall purpose of the essay: to come to a compromise about the issue at hand. If this intent is not stated up front, the reader may be confused or even suspect manipulation on the part of the writer, i.e., that the writer is massaging the audience just to win a fight. Be advised that the Rogerian essay uses an inductive reasoning structure, so do not include your thesis in your introduction. You will build toward the thesis and then include it in your conclusion. Once again, state the intent to compromise, but do not yet state what the compromise is.

2. Side A: Carefully map out the main claim and reasoning for the opposing side of the argument first. The writer’s view should never really come first because that would defeat the purpose of what Rogers called empathetic listening, which guides the overall approach to this type of argument. By allowing the opposing argument to come first, you communicate to the reader that you are willing to respectfully consider another’s view on the issue. Furthermore, you invite the reader to then give you the same respect and consideration when presenting your own view. Finally, presenting the opposition first can help those readers who would side against you to ease into the essay, keeping them invested in the project. If you present your own ideas first, you risk polarizing those readers from the start, which would then make them less amenable to considering a compromise by the end of the essay. You can listen to Carl Rogers himself discuss the importance of empathy on YouTube (https://youtu.be/2dLsgpHw5x0, transcript here).

3. Side B: Carefully go over your side of the argument. When mapping out this side’s claim and support, be sure that it parallels that of Side A. In other words, make sure not to raise entirely new categories of support, or there can be no way to come to a compromise. Make sure to maintain a non-confrontational tone; for example, avoid appearing arrogant, sarcastic, or smug.

4. The Bridge: A solid Rogerian argument acknowledges the desires of each side and tries to accommodate both. In this part, point out the ways in which you agree or can find common ground between the two sides. There should be at least one point of agreement. This can be an acknowledgement of the one part of the opposition’s agreement that you also support or an admittance to a shared set of values even if the two sides come to different ideas when employing those values. This phase of the essay is crucial for two reasons: finding common ground (1) shows the audience the two views are not necessarily at complete odds, that they share more than they seem, and (2) sets up the compromise to come, making it easier to digest for all parties. Thus, this section builds a bridge from the two initial isolated and opposite views to a compromise that both sides can reasonably support.

5. The Compromise: Now is the time to finally announce your compromise, which is your thesis. The compromise is what the essay has been building towards all along, so explain it carefully and demonstrate the logic of it. For example, if debating about whether to use racial profiling, a compromise might be based on both sides’ desire for a safer society. That shared value can then lead to a new claim, one that disarms the original dispute or set of disputes. For the racial profiling example, perhaps a better solution would focus on more objective measures than race that would then promote safety in a less problematic way.

Figure 6.2 “Rogerian Argument”

Sample Writing Assignment

Find a controversial topic, and begin building a Rogerian argument. Write up your responses to the following:

- The topic or dilemma I will write about is…

- My opposing audience is…

- My audience’s view on the topic is…

- My view on the topic is…

- Our common ground–shared values or something that we both already agree on about the topic–is…

- My compromise (the main claim or potential thesis) is…

Reading Strategies for a Rogerian Argument

To create a Rogerian Argument, you need to understand your opponent’s ideas deeply, and it also helps to understand your own side of the issue in depth. You already learned important skills for reading an argument, understanding an argument, and summarizing an argument. In addition to those skills, here are two new strategies: reading as a Believer and reading as a Doubter. As you can imagine, the first strategy is most relevant for a Rogerian Argument.

Believing and Doubting Games in Reading

When one thinks of reading the first thing that pops into mind is a person holding a book sitting in an easy chair in front of a fire lost in the author’s world, sailing the sea with captain Ahab, roaming the south with Faulkner, floating down the Mississippi with Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, reading as a kind of vacation from the real world. Reading is an escape into our imagination and the words and sentences of the writer. We are not tested on this reading or expected to argue about its literary merits. It is not work or pragmatic, it is pleasure, entertainment.

We read now from phones, computers, Nooks, wide screen color televisions, and movie screens as well as books and journals, and much of our reading in school is for a pragmatic purpose. For the purpose of this composition course we will use reading for inquiry (truth seeking) and persuasion (rhetoric).

Methods of Reading

Skimming

Skimming is valuable when you are choosing your sources. It involves reading the abstract, the first paragraph, the last paragraph, and gliding or passing quickly through the body paragraphs.

Reading to find the truth about an issue

A good way of reading to explore and find the truth about an issue (inquiry) is by playing the believing and doubting game developed by Peter Elbow.

Believing Game

Close Reading and Summary Writing as a Way to Play the Believing Game

a. A says statement summarizes the content of the paragraph or main idea of the paragraph in your own words.

b. A does statement summarizes the paragraphs function. Does the paragraph state the main claim or present reasons or evidence? Does the paragraph address the opposition or conclude the argument? Does it use humor or quote another author?

Doubting Game

The doubting game seeks truth by indirection – by seeking error. Doubting an assertion is the best way to find error in it. You must assume it is untrue if you want to find its weakness. The truer it seems, the harder you have to doubt it. Non credo ut intelligam: in order to understand what’s wrong, I must doubt.

To doubt well, it helps if you make a special effort to extricate yourself from the assertions in question – especially those which you find self-evident. You must hold off to one side the self, its wishes, preconceptions, experiences, and commitments. (The machinery of symbolic logic helps people do this.) Also, it helps to run the assertion through logical transformations so as to reveal premises and necessary consequences and thereby flush out into the open any hidden errors. You can also doubt better by getting the assertions to battle each other and thus do some of the work: They are in a relationship of conflict, and getting them to wrestle each other, you can utilize some of their energy and cleverness for ferreting out weakness.

Peter Elbow

Dialectic Thinking

Dialectic or dialectics (Greek: διαλεκτική, dialektikḗ), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to establish the truth through reasoned arguments.

Because it’s so hard to let go of an idea we are holding (or more to the point, an idea that’s holding us), our best hope for leverage in learning to doubt such ideas is to take on different ideas. Peter Elbow

Key Takeaways

Questions to Ask

- How do the two arguers disagree about the facts and interpretation of facts?

- How are their beliefs, values, and assumptions different?

- Do they have shared beliefs, values and assumptions?

- How have my own beliefs, values, and assumptions changed? Have I been exposed to new ideas? How have my views changed?

Chapter Attribution

The material in this chapter is slightly modified (derivative) and includes material from the following sources:

“The Rogerian Argument” in Let’s Get Writing! by Kirsten DeVries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Believing and Doubting Games in Reading” from Writing and Rhetoric by Heather Hopkins Bowers; Anthony Ruggiero; and Jason Saphara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Image Attributions from Let’s Get Writing!

Figure 6.1 “Carl Ransom Rogers,” by Didius, Wikimedia, CC-BY 2.5.

Figure 6.2 “Rogerian Argument,” by Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.