Introducing the Argument and Main Claim

Introducing the Argument

Almost immediately, the reader of any summary will need some basic information about the argument summarized. We can name title and author in an introductory phrase. If the publication date and the publication name seem important, we can work those in too. For example, a summary could introduce the basic data on the sample border argument with the phrase "In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills..." and follow it with a description of the topic, purpose, or main claim. Some options for introductory phrases include the following:

- In an article for _____________, writer _____________...

- The account of _____________ in the piece _____________ by _____________...

- Writing in the journal _____________, the scholar _____________ ...

Next, probably right after the introductory phrase, the reader will want to know the main point of that argument. To introduce the main claim, we’ll need a well-chosen verb to describe the author’s intention, her purpose in writing. The most general possible verb to describe a main claim would be “says,” as in “In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills says… ” But that would tell us so little about what Anna Mills is trying to do. Readers will be bored and will learn nothing from “says.” If we choose a more dramatic and precise verb like “calls for,” “criticizes,” “describes,” “argues,” or “questions,” then readers will feel the dynamism and momentum of both the argument and the summary. We can convey a lot about the structure of the argument, its degree of conviction or moderation, its tone and attitude by the word or phrase we choose to introduce each claim. As we choose those phrases, we will also be pushing ourselves to get an even clearer picture of the argument than we did by mapping it.

Describing Claims of Fact

If the argument’s main purpose is to describe reality in some way, we will want to let readers know if it is controversial or not. Is the writer defending their idea against obvious objections or counterarguments, or are they aiming to inform us about something we may not be aware of?

Phrases to introduce controversial claims of fact

- They argue that _____________.

- She maintains that _____________.

- He contends that _____________.

- They assert that _____________.

- She holds that _____________.

- He insists that _____________.

- She thinks_____________.

- They believe that_____________.

Phrases to introduce widely accepted claims of fact

- He informs us of _____________.

- She describes_____________.

- They note that _____________.

- He observes that _____________.

- She explains that _____________.

- The writer points out the way in which_____________.

Describing Claims of Value

If the argument’s main purpose is to convince us that something is bad or good or of mixed value, we can signal that evaluation to the reader right off the bat. How dramatic is the claim about its praise or critique? We can ask ourselves how many stars the argument is giving the thing it evaluates. A five-star rating “celebrates” or “applauds” its subject while a four-star rating might be said to “endorse it with some reservations.”

Phrases to describe a positive claim of value

- They praise_____________.

- He celebrates_____________.

- She applauds the notion that_____________.

- They endorse_____________.

- He admires_____________.

- She finds value in_____________.

- They rave about_____________.

Phrases to describe a negative claim of value

- The author criticizes_____________.

- She deplores____________.

- He finds fault in_____________.

- They regret that_____________.

- They complain that_____________.

- The authors are disappointed in_____________.

Phrases to describe a mixed claim of value

- The author gives a mixed review of_____________.

- She sees strengths and weaknesses in_____________.

- They endorse_____________ with some reservations.

- He praises_____________ while finding some fault in _____________

- The authors have mixed feelings about_____________. On the one hand, they are impressed by_____________, but on the other hand, they find much to be desired in_____________.

Describing Claims of Policy

If, as in the case of our sample argument, the author wants to push for some kind of action, then we can signal to the reader how sure the writer seems of the recommendation and how much urgency they feel. Since the border argument uses words like “must” and “justice” in its final paragraph, we will want to convey that sense of moral conviction if we can, with a verb like “urges.” Here is one possible first sentence of a summary of that argument:

In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills urges us to seek a new border policy that helps desperate migrants rather than criminalizing them.

If we think there should be even more sense of urgency, we might choose the verb “demands.” “Demands” would make Mills seem more insistent, possibly pushy. Is she that insistent? We will want to glance back at the original, probably many times, to double-check that our word choice fits.

If the border argument ended with a more restrained tone, as if to convey politeness and humility or even uncertainty, we might summarize it with a sentence like the following:

In her 2019 article 'Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?', Anna Mills asks us to consider how we can change border policy to help desperate undocumented migrants rather than criminalizing them.

Phrases to describe a strongly felt claim of policy

- They advocate for_____________.

- She recommends_____________.

- They encourage_____________to _____________.

- The writers urge_____________.

- The author is promoting_____________.

- He calls for_____________.

- She demands_____________.

Phrases to describe a more tentative claim of policy

- He suggests_____________.

- The researchers explore the possibility of_____________.

- They hope that_____________can take action to_____________.

- She shows why we should give more thought to developing a plan to_____________.

- The writer asks us to consider_____________.

Elaborating on the Main Claim

Depending on the length of the summary we are writing, we may add in additional sentences to further clarify the argument’s main claim. In the border argument example, the summary we have thus far focuses on the idea of helping migrants, but the argument itself has another, related dimension which focuses on the attitudes we should take toward migrants. If we are asked to write only a very short summary, we might leave the explanation of the main claim as it is. If we have a little more leeway, we might add to it to reflect this nuance thus:

In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills urges us to seek a new border policy that helps desperate undocumented migrants rather than criminalizing them. She calls for a shift away from blame toward respect and empathy, questioning the very idea that crossing illegally is wrong.

Of course, the border argument is short, and we have given an even briefer summary of it. College courses will also ask us to summarize longer, multi-part arguments or even a whole book. In that case, we will need to summarize each sub-section of the argument as its own claim.

Exercise

For each claim below, decide whether it is a claim of fact, value, or policy. Write a paraphrase of each claim and introduce it with a phrase that helps us see the writer’s purpose.

-

Students should embrace coffee to help them study.

-

Coffee is the most powerful, safe substance available to jumpstart the mind.

-

Coffee’s effect is universal.

-

For those of us who believe in the life of the mind, enhancing our brains’ abilities is ultimately worth the occasional discomfort associated with coffee.

Describing the Reasoning

Once we have introduced the argument we will summarize and described its main claim, we will need to show how it supports this claim. How does the writer point us in the direction they want us to go? Whereas we used an arrow in the argument map to show momentum from reason to claim, we can use a phrase to signal which idea serves as a reason for which claim.

Phrases for Introducing Reasons

- She reasons that _____________.

- He explains this by_____________.

- The author justifies this with_____________.

- To support this perspective, the author points out that_____________.

- The writer bases this claim on the idea that_____________.

- They argue that_____________ implies that _____________ because_____________.

- She argues that if _____________, then _____________.

- He claims that _____________ necessarily means that_____________ .

- She substantiates this idea by_____________.

- He supports this idea by_____________.

- The writer gives evidence in the form of_____________.

- They back this up with_____________.

- She demonstrates this by_____________.

- He proves attempts to prove this by _____________.

- They cite studies of _____________.

- On the basis of _____________, she concludes that _____________.

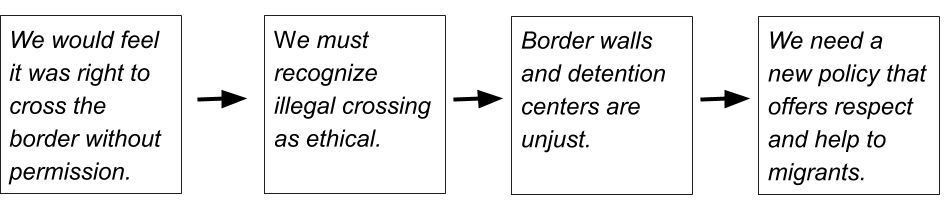

Our border argument map shows a chain of three reasons leading to the main claim, so our summary can describe that chain.

Sample summary

In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills urges us to seek a new border policy that helps desperate undocumented migrants rather than criminalizing them. She calls for a shift toward respect and empathy, questioning the very idea that crossing illegally is wrong. She argues that any parent in a desperate position would consider it right to cross for their child’s sake; therefore, no person should condemn that action in another. Since we cannot justify our current walls and detention centers, we must get rid of them.

Practice Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

For each pair of claims and reasons below, write a paraphrase of the reason and introduce it with one of the phrases from the chapter or another phrase that serves a similar purpose.

Here's an example. Take the following claim and reason pair: “The right of free speech does not apply to speech that endangers public health. Therefore, Twitter should not allow tweets that promote medical claims that have been proven wrong.”

A description of the reason might read as follows: "The writer bases this recommendation on the idea that we do not have a free-speech right to spread ideas that harm other people’s health."

-

"Coffee jumpstarts the mind. Therefore, students should embrace coffee to help them study."

-

"Students should avoid coffee. Relying on willpower alone to study reinforces important values like responsibility and self-reliance."

-

"Students should drink black tea rather than coffee because tea has fewer side effects."

Describing How the Author Treats Counterarguments

If the argument we are summarizing mentions a counterargument, a summary will need to describe how the author handles it. A phrase introducing the author's treatment of the counterargument can signal whether the writer sees some merit in the counterargument or rejects it entirely. In either case, we will almost always want to follow up by describing the author’s response. If the writer sees merit in the objection, we need to explain why they still maintain their position. On the other hand, if the author dismisses the counterargument, we need to show how they justify this dismissal.

Phrases to Introduce a Writer's Handling of a Counterargument

If the Author Sees Some Merit in the Counterargument

- The writer acknowledges that _____________, but still insists that _____________.

- They concede that _____________; however they consider that _____________.

- He grants the idea that _____________, yet still maintains that _____________.

- She admits that _____________, but she points out that_____________.

- The author sees merit in the idea that _____________, but cannot accept_____________.

- Even though he sympathizes with those who believe _____________, the author emphasizes that _____________.

If the Author Rejects the Counterargument Entirely

- She refutes this claim by arguing that _____________.

- However, he questions the very idea that _____________, observing that _____________.

- She disagrees with the claim that _____________ because _____________.

- They challenge the idea that _____________ by arguing that _____________.

- He rejects the argument that_____________, claiming that _____________.

- She defends her position against those who claim _____________ by explaining that _____________.

In the case of the sample border argument, we might summarize the treatment of the counterargument thus:

Mills acknowledges that opening the borders completely would compromise security, but she believes that we can “regulate” our borders without blocking or imprisoning migrants.

Note the choice here to quote the one word “regulate” instead of paraphrasing or using the word without quotation marks. The quotation marks draw attention to the author's original word choice and suggest there may be a problem or question about this word choice. In this case, the summary might observe that the writer does not specify what kind of regulation she means.

Exercise

Below are two sample paragraphs in which an author describes a counterargument. For each description, decide whether the author sees some merit in the counterargument or not (see 2.6). Choose a phrase from the suggestions above to help you summarize the author’s handling of the counterargument.

- Not everyone agrees with my celebration of coffee. Some object that ingesting substances to help us study leads to addiction. They worry that even a boost to mental functioning will ultimately hurt us because it encourages us to try to fix our mind with substances any time we feel out of sorts. This argument, however, is nothing short of paranoid. It would result in some ridiculous conclusions. By its logic, we should not drink water when we’re thirsty because we will become addicted.

- Many feel that black tea is a better choice than coffee, arguing that it can improve performance just as well with fewer side effects. This depends on the individual, though. While black tea is worth considering, remember that it can also have side effects, and for many, it simply will not give enough of a boost to the brain.

Describing How the Author Limits the Claim

In the course of describing the author’s claims, reasons, and counterarguments, chances are we will already have mentioned some limits or clarified which kinds of cases an author is referring to. It is worth checking, however, to make sure we haven’t left out any key limitations the author has identified.

Phrases to Describe the Way a Writer Limits an Argument

- He qualifies his position by_____________.

- She limits her claim by_____________.

- They clarify that this only holds if _____________.

- The author restricts their claim to cases where_____________.

- He makes an exception for_____________.

In the case of the border argument, the writer responds to the counterargument about security by clarifying that she does not advocate completely open borders. The sample summary already refers to this when it describes her desire to “regulate” those borders. In addition, when it paraphrases her claims and reasons, it uses the phrases “desperate” and “in a desperate position” to limit the focus to migrants who are fleeing an awful situation.

Exercises

Below are some sample claims that mention limits. Choose one of the phrases above or create another one with a similar purpose to help you summarize each claim and limit.

-

Students should embrace coffee to enhance mental functioning unless they are in the minority of people who experience severe side effects of coffee like anxiety, insomnia, tremors, acid reflux, or a compulsion to drink more and more.

-

Students shouldn’t hesitate to enjoy coffee as long as they keep exercising and sleeping well enough to maintain their mental and physical health.

-

In moderation, coffee can be part of a healthy lifestyle.

Putting the Summary Together

How can we turn the descriptions of the claims, reasons, counterarguments, and limitations into a cohesive paragraph, page, or essay that we can turn in as our summary? The good news is that by introducing each part of the argument to show how it relates to the others, we have already provided many of the transitions we need. We can generate a first draft of the summary by simply putting them all together in order. Here is what such a draft would look like for the border argument:

Sample Summary

In her 2019 article “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”, Anna Mills urges readers to seek a new border policy that helps desperate undocumented migrants rather than criminalizing them. She calls for a shift toward respect and empathy, questioning the very idea that crossing illegally is wrong. Mills argues that any parent in a desperate position would consider it right to cross for their child’s sake; therefore, no person should condemn that action in another. Since we cannot justify our current walls and detention centers, we must get rid of them. She acknowledges that opening the borders completely would compromise security, but believes that we can still “regulate” our borders without blocking or imprisoning migrants.

Next, we can review our border argument map to make sure that we have covered the main parts of the argument.

![The top half of the graphic is a chain of reasons. The first reason "We would feel it was right to cross the border without permission" is in a box with an arrow next to it pointing to the next reason, "We should recognize illegal crossing as ethical," which in turn has an arrow from it pointing to the reason "Border walls and detention centers are unjust," which points to the final claim, "We need a new policy that offers respect and help to migrants." Below, in red, with an arrow pointing up toward the final claim, is the counterargument "Completely open borders would put our security at risk." Below the counterargument, the response to the counterargument has been changed to blue, and the response is labeled “Rebuttal/Limit: there are ways to regulate the border without criminalizing people." This response still has an arrow from it pointing up toward the main claim to show that it supports the main claim. In addition, two limits in blue type have been added. The text “[Limit: If we were in desperate circumstances]” has a blue arrow pointing upward to the first reason to indicate that it modifies the statement “We would feel it was right to cross the border without permission." Next to it, the text “[Limit: If migrants cross because of desperate circumstances]” has an arrow pointing up to indicate that it limits the second reason, “"We should recognize illegal crossing as ethical."](https://spscc.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/144/2022/05/image5-1.png)

If we are writing a longer summary of an extended argument, our map and our knowledge of the role of each part of the text will help us organize the essay into paragraphs and transition between them. For example, in a three-page summary of a twenty-five-page essay, we might spend a full paragraph on the author’s description of a counterargument and yet another paragraph on the author’s rebuttal to this counterargument. To open this paragraph, we could refer to our earlier list of templates for describing a response to a counterargument.

Practice Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Summarize the argument below in a few sentences that introduce each element of the argument and its role. If you completed the exercises for the earlier sections in this chapter, you may use some of those answers to those to help you put together this paragraph.

Coffee is a blessing to students. What better way is there to jumpstart the mind and help us engage with our studies? The benefits of coffee are well known, and yet some hold back from it unnecessarily. Some feel that black tea is a better choice, arguing that it can still boost mental performance with fewer side effects. This depends on the individual. While black tea is worth considering, remember that it still comes with side effects, and for many, it simply will not give enough of a boost to the brain. For those of us who believe in the life of the mind, enhancing our brains’ abilities is ultimately of more value than avoiding the occasional minor discomfort. Of course, a few people who experience severe side effects like anxiety, insomnia, or tremors should avoid coffee. For most, though, we can drink coffee in moderation and still feel healthy, as long as we exercise and sleep well. Some object to coffee because they believe that ingesting any substance to help us study leads to addiction. They worry that even a boost to mental functioning will ultimately hurt us because it encourages us to try to fix our mind with substances any time we feel out of sorts. This argument, however, is nothing short of paranoid. It would result in some ridiculous conclusions. By its logic, if we drink water when we’re thirsty, we will end up addicted. If you haven’t given coffee a fair try under the right circumstances, don’t deprive yourself out of fear. Chances are you can do better work and enjoy it more with a moderate coffee habit. Why let life’s “Aha” moments pass you by?

Writing a Short Summary of a Long Argument

Thus far we have given examples of summaries that are close in length to the original argument. Very often in college and professional life, though, we will need to summarize a multi-page argument in just a sentence, a paragraph, or a page. How do we cover the most important ideas of the argument in just a few words? How do we decide what to leave out of the summary?

If we have already sorted out which ideas are the supporting examples and statistics and which are the main claim and reasons, that knowledge can guide us. The summary can allude to the supporting evidence rather than describing its details. It can leave out the specifics of any anecdotes, testimonials, or statistics.

For example, let's imagine we want to summarize an article that encourages people to buy the digital cryptocurrency BitCoin. The article might describe a number of different kinds of products people can buy with BitCoin and tell stories of individuals who used BitCoin for different purposes or invested in BitCoin and made a profit. Depending on how long our summary is supposed to be, we can represent those parts of the argument in more or less detail. If we need to summarize the article in a sentence, we might simply refer to all of this supporting evidence with a couple of words like "variety" and "profit."

Example

Sample one-sentence summary: "Go BitCoin" by Tracy Kim encourages the general public to buy BitCoin by showing us the variety of things we can buy with it and the profit to be made."

If we have a bit more space, we might keep the same single-sentence overview but also throw in a few examples of the kinds of specifics mentioned in the article.

Example

Sample slightly longer summary: "Go BitCoin" by Tracy Kim encourages the general public to buy BitCoin by showing us the variety of things we can buy with it and the profit to be made. First, Kim describes how we would go about paying for a range of products, from a Tesla to a sofa. Second, she gives statistics on BitCoin's rate of return and tells the stories of three young people who invested modest amounts in BitCoin and saw their money as much as triple within a year.

Notice how, in the above example, the summary alludes to three stories that have something in common but gives a detail that only applies to one of them. The summary writer chose the most memorable example of profit to include. If we have space to write a full paragraph, we could include more detail on the process of buying with bitcoin, on the investment statistics alluded to, and on the stories of investors.

Example

Sample paragraph-long summary: "Go BitCoin" by Tracy Kim encourages the general public to buy the cryptocurrency BitCoin by showing us the variety of things we can buy with it and the profit to be made. First, Kim describes how we would go about paying for a range of products, from a Tesla to a sofa. She shows how more and more vendors are accepting BitCoin directly, but for the moment some of the largest ones, like Amazon, require buyers to use a third-party app to convert their BitCoin. Second, she gives statistics on BitCoin's rate of return. BitCoin has gone through boom and bust cycles, but most recently its value increased 252% between July 2020 and July 2021. Finally, she tells the stories of three young people who invested modest amounts in BitCoin and saw their money as much as triple within a year. Kim shows how ordinary people can see more options open up in their lives through these investments. One teenager, Vijay Mather, was able to cover four years of college tuition by investing his earnings from working at Trader Joe's.

The original argument would include many more details, including how Vijay Mather got interested in BitCoin and exactly how much he made on his investment. It probably also includes the names of the other two young people it profiles and more about their experiences. However, the summary writer has picked out what those experiences have in common--the fact that the profits allowed them to consider new options in their lives. The writer has focused on Tracy Kim's purpose in presenting those examples: to raise readers' awareness of the possibilities.

Exercises

Read the two paragraphs below.

- Summarize them in just one sentence.

- Summarize them in two to three sentences, including a few more specifics.

The Black/white binary is the predominant racial binary system at play in the American context. We can see that this Black/white binary exists and is socially constructed if we consider the case of the 19th Century Irish immigrant. When they first arrived, Irish immigrants were “blackened” in the popular press and the white, Anglo-Saxon imagination (Roediger 1991). Cartoon depictions of Irish immigrants gave them dark skin and exaggerated facial features like big lips and pronounced brows. They were depicted and thought to be lazy, ignorant, and alcoholic nonwhite “others” for decades.

Over time, Irish immigrants and their children and grandchildren assimilated into the category of “white” by strategically distancing themselves from Black Americans and other non-whites in labor disputes and participating in white supremacist racial practices and ideologies. In this way, the Irish in America became white. A similar process took place for Italian-Americans, and, later, Jewish American immigrants from multiple European countries after the Second World War. Similar to Irish Americans, both groups became white after first being seen as non-white. These cases show how socially constructed race is and how this labeling process still operates today. For instance, are Asian-Americans, considered the “model minority,” the next group to be integrated into the white category, or will they continue to be regarded as foreign threats? Only time will tell.

Sample Summaries

- In "Typography and Identity," Saramanda Swigart summarizes the New York Times article “A Debate Over Identity and Race Asks, Are African-Americans ‘Black’ or ‘black’?” Annotations point out the structure of the summary and the strategies Swigart uses.

Screen-Reader Accessible Sample Summary 1

Format note: This version is accessible to screen reader users. Refer to these tips for reading our annotated sample arguments with a screen reader. For a more traditional visual format, see the PDF version above.

Gizem Gur

Eng 1A

Anna Mills

Spread Feminism, Not Germs

COVID-19 is not the first outbreak in history and probably won’t be the last one. (Note: The opening statement provides the essay's overall context: the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.) However, its effects will be long-lasting. While the pandemic has affected everyone’s lives in every aspect, its impacts on women are even more severe. (Note: The followup statement introduces the essay's particular focus: the impact of the pandemic on women.) Helen Lewis, the author of the Atlantic Magazine article “The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism,” explains why the pandemic threatens feminism. (Note: Early on, the summary names the author, title, and magazine that published the argument summarized.) Lewis starts her article with a complaint by saying “enough already” because, in terms of housework especially for child care, there has been an inequality since the past. This inequality has become even more explicit with the coronavirus outbreak. Women have to shoulder not only more housework but also childcare more than ever due to school closures. The pandemic started as a public health crisis and brought along an economic one. Lewis argues that the crisis affects women more than men because women are more likely to assume housework and childcare responsibilities while men are expected to work and “bring home the bacon.” (Note: The author provides a thesis at the end of the introduction with a clear overview of the main claim of the argument summarized.)

Lewis supports her claim by pointing out that during the pandemic, the gender pay gap pushes women to take on caregiving while men continue to work outside the home. (Note: The phrase "supports her claim" shows us that this paragraph will describe one of Lewis' reasons.) She writes, “all this looking after—this unpaid caring labor—will fall more heavily on women" because households depend more on men's pay. To support this idea, she includes provocative questions from Clare Wenham, an assistant professor of global health policy at the London School of Economics: “Who is paid less? Who has the flexibility?” (Note: The author supports the summary with short quotes from the argument where the wording is important.) The questions express Wenham's frustration. Lewis implies that this existing structure is based upon the gender pay gap, the reality that women make less money. She believes that couples do not have many options: it is a kind of survival rule that whoever earns less should stay at home.

Lewis blames the influence of old-fashioned ideas about gender roles for compounding the effects of the pay gap during the pandemic. Dual-earner parents must find a way to meet children’s needs during the shelter-in-place. Lewis observes that women often are the ones who take on the role of stay-at-home parent. (Note: This paragraph shows how another reason, gender role expectations, combines with the economic reason to support the main claim.) She humorously notes, “Dual-income couples might suddenly be living like their grandparents, one homemaker, and one breadwinner.” Lewis sees this as a kind of embarrassing regression. The gender dynamic has slid back two generations, showing that cultural beliefs about the role of the mother haven't changed as much as we might think. (Note: The use of the word "embarrassing" suggests that Lewis is not just observing but making a claim of value. The summary reflects Lewis' attitude as well as her ideas.) Lewis acknowledges that some families do try to split childcare equally, but she emphasizes that these are in the minority.

Lewis sees implications for her claim beyond the current pandemic. (Note: The end of the summary notes how Lewis extends her argument by claiming that other pandemics will have similar gendered effects.) She draws a parallel to the effect on women of the Ebola health crisis which occurred in West Africa in the time period of 2014-2016. According to Lewis, during this outbreak, many African girls lost their chance at an education; moreover, many women died during childbirth because of a lack of medical care. (Note: Lewis supports this with a historical example of another pandemic that disproportionately hurt women.) Mentioning this proves that not only coronavirus but also other outbreaks can be a disaster for feminism. Pandemics, in other words, pile yet another problem on women who always face an uphill battle against patriarchal structures. (Note: The concluding sentence reinforces the extended version of Lewis' main point in a memorable, dramatic way.)

Attribution

This sample essay was written by Gizem Gur and edited by Anna Mills. Annotations are by Saramanda Swigart, edited by Anna Mills. Licensed under a CC BY-NC license.

Screen-reader Accessible Version of Sample Summary 2

Format note: This version is accessible to screen reader users. Refer to these tips for reading our annotated sample arguments with a screen reader. For a more traditional visual format, see the PDF version above.

Essay Z

English 1C

Prof. Saramanda Swigart

Typography and Identity

John Eligon's New York Times article, “A Debate Over Identity and Race Asks, Are African-Americans ‘Black’ or ‘black’?” outlines the ongoing conversation among journalists and academics regarding conventions for writing about race—specifically, whether or not to capitalize the “b” in “black” when referring to African-Americans (itself a term that is going out of style). (Note: The opening sentence introduces the text this essay will respond to and gives a brief summary of the text's content.) Eligon argues that, while it might seem like a minor typographical issue, this small difference speaks to the question of how we think about race in the United States. Are words like “black” or “white” mere adjectives, descriptors of skin color? Or are they proper nouns, indicative of group or ethnic identity? Eligon observes that until recently, with the prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement, many journalistic and scholarly publications tended to use a lowercase “black,” while Black media outlets typically capitalized “Black.” He suggests that the balance is now tipping in favor of "Black," but given past changes, usage will probably change again as the rich discussion about naming, identity, and power continues. (Note: The thesis statement includes two related ideas explored by Eligon: the current trend toward using "Black" and the value of the ongoing discussion that leads to changing terms.)

Eligon points to a range of evidence that "Black" is becoming the norm, including a recent change by "hundreds of news organizations" including the Associated Press. This comes in the wake of the George Floyd killing, but it also follows a longtime Black press tradition exemplified by newspapers like The New York Amsterdam News. Eligon cites several prominent academics who are also starting to capitalize Black. However, he also quotes prominent naysayers and describes a variety of counterarguments, like the idea that capitalization gives too much dignity to a category that was made up to oppress people. (Note: Summary of a counterargument.) Capitalizing Black raises another tricky question: Shouldn't White be likewise capitalized? Eligon points out that the groups most enthusiastic to capitalize White seem to be white supremacists, and news organizations want to avoid this association. (Note: The choice of "points out" signals that everyone would agree that mostly white supremacist groups capitalize White.)

Eligon's brief history of the debate over racial labels, from “Negro” and “colored” to “African-American” and “person of color,” gives the question of to-capitalize-or-not-to-capitalize a broader context, investing what might seem like a minor quibble for editors with the greater weight of racial identity and its evolution over time. (Note: This paragraph shifts focus from present to past trends and debates.) He outlines similar disagreements over word-choice and racial labels by scholars and activists like Fannie Barrier Williams and W.E.B. Du Bois surrounding now-antiquated terms like “Negro” and “colored.” These leaders debated whether labels with negative connotations should be replaced, or embraced and given a new, positive connotation. (Note: This paragraph summarizes the historical examples Eligon gives. Phrases like "He cites" point out that certain ideas are being used to support a claim.) Eligon observes that today's "black" was once used as a pejorative but was promoted by the Black Power movement starting in the late sixties, much as the word "Negro" was reclaimed as a positive word. (Note: Summary of a historical trend that parallels today's trend.) However, the Reverend Jesse Jackson also had some success in calling for a more neutral term, "African American," in the late eighties. He thought it more appropriate to emphasize a shared ethnic heritage over color. (Note: Summary of a historical countertrend based on a counterargument to the idea of reclaiming negative terms.) Eligon suggests that this argument continues to appeal to some today, but that such terms have been found to be inadequate given the diversity of ethnic heritage. “African-American” and the more generalized “people/person of color” do not give accurate or specific enough information. (Note: Describes a response to the counterargument, a justification of today's trend toward Black.)

Ultimately, Eligon points to personal intuition as an aid to individuals in the Black community grappling with these questions. He describes the experience of sociologist Crystal M. Fleming, whose use of lowercase “black” transformed to capitalized “Black” over the course of her career and years of research. Her transition from black to Black is, she says, as much a matter of personal choice as a reasoned conclusion—suggesting that it will be up to Black journalists and academics to determine the conventions of the future. (Note: This last sentence of this summary paragraph focuses on Eligon's conclusion, his implied argument about what should guide the choice of terms.

Works Cited

(Note: The Works Cited page uses MLA documentation style appropriate for an English class.)

Eligon, John. “A Debate Over Identity and Race Asks, Are African-Americans ‘Black’ or ‘black’?” The New York Times, 26 Jun 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/us/black-african-american-style- debate.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage

Attribution

This sample essay was written and annotated by Saramanda Swigart and edited by Anna Mills. Licensed CC BY-NC 4.0.

Chapter Attribution