LO 12.4 Describe the Balanced Scorecard and Explain How It Is Used

The performance measures considered up to this point have relied only on financial accounting measures as the means to evaluate performance. Over time, the trend has become to incorporate both quantitative and qualitative measures and short- and long-term goals when evaluating the performance of managers as well as the company as a whole. One approach to evaluating both financial and nonfinancial measures is to use a balanced scorecard.

History and Function of the Balanced Scorecard

Suppose you work in retail and your compensation consists of an hourly wage plus a bonus based on your sales. You have excellent interpersonal skills, and customers appreciate your help and often seek you out when they come to the store. Some of your customers will return on a different day, even making an extra trip to the store to make sure you are the employee who helps them. Sometimes these customers buy items and other times they do not, but they always come back. Your compensation does not include any acknowledgment of your attention to customers and your ability to keep them returning to the store, but consider how much more you could earn if this were the case. However, in order for compensation to include nonfinancial, or qualitative, factors, the store would need to track nonfinancial information, in addition to the financial, or quantitative, information already tracked in the accounting system. One way to track both qualitative and quantitative measures is to use a balanced scorecard.

The idea for using a balanced scorecard to evaluate employees was first suggested by Art Schneiderman of Analog Devices in 1987 as a means to improve corporate performance by using metrics to measure improvements in areas in which Analog Devices was struggling, such as in a high number of defects. Schneiderman went through different iterations of a balanced scorecard design over several years, but the final design chosen measured three different categories: financial, customer, and internal. The financial category included measures such as return on assets and revenue growth, the customer category included measures such as customer satisfaction and on-time delivery, and the internal category included measures such as reduced defects and improved throughput time. Eventually, Robert Kaplan and David Norton, both Harvard University faculty, expanded upon Schneiderman’s ideas to create the current concept of the balanced scorecard and four general categories for evaluation: financial perspective, customer perspective, internal perspective, and learning and growth. These categories are sometimes modified for particular industries.

Therefore, a balanced scorecard evaluates employees on an assortment of quantitative factors, or metrics based on financial information, and qualitative factors, or those based on nonfinancial information, in several significant areas. The quantitative or financial measurements tend to emphasize past results, often based on their financial statements, while the qualitative or nonfinancial measurements center on current results or activities, with the intent to evaluate activities that will influence future financial performance.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Managers and employees generally strive to create and work in an ethical environment. In order to develop such an environment, employees need to be informed of the organization’s ethical standards and values and have an understanding of the laws and regulations under which the organization operates. If employees do not know the standards by which they will be measured, they might not be aware if their behavior is ethical. A balanced scorecard allows employees to understand their organization’s obligations, and to evaluate their own obligations in the workplace.

To evaluate their ethical environment, organizations can hold meetings that use ethical analysis metrics. Kaplan and Norton, leaders in balanced scorecard use, explain the use of the balanced scorecard in the context of strategy review meetings: Companies conduct strategy review meetings to discuss the indicators and initiatives from the unit’s Balanced Scorecard and assess the progress of and barriers to strategy execution.1 In such meetings, the metrics analyzed should include, but not be limited to, the availability of a hotline; employee participation in ethics training; satisfaction of customers, employees, and other stakeholders; employee turnover rate; regulation compliance; community involvement; environmental awareness; diversity; legal expenses; efficient asset usage; condition of assets; and social responsibility.2 Metrics should be tailored to an organization’s values and desired operational results. The use of a balanced scorecard helps lead to an ethical environment for employees and managers.

Four Components of a Balanced Scorecard

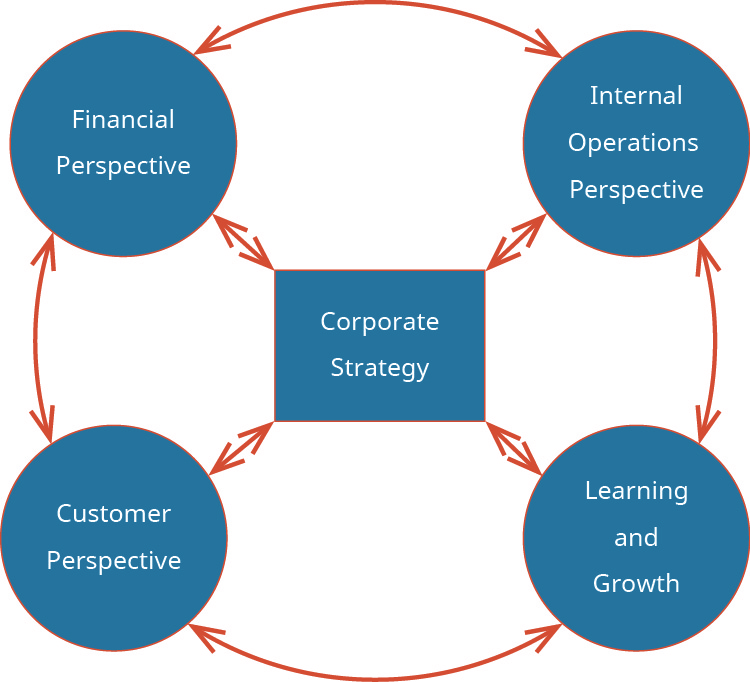

To create a balanced scorecard, a company will start with its strategic goals and organize them into key areas. The four key areas used by Kaplan and Norton were financial perspective, internal operations perspective, customer perspective, and learning and growth ((Figure)).

These areas were chosen by Kaplan and Norton because the success of a company is dependent on how it performs financially, which is directly related to the company’s internal operations, how the customer perceives and interacts with the company, and the direction in which the company is headed. The use of the balanced scorecard allows the company to take a stakeholder perspective as compared to a stockholder perspective. Stockholders are the owners of the company stock and often are most concerned with the profitability of the company and thus focus primarily on financial results. Stakeholders are people who are affected by the decisions made by a company, such as investors, creditors, managers, regulators, employees, customers, suppliers, and even laypeople who are concerned about whether or not the company is a good world citizen. This is why social responsibility factors are sometimes included in balanced scorecards. To understand where these types of factors might fit in a balanced scorecard framework, let’s look at the four sections or categories of a balanced scorecard.

Financial Perspective

The financial performance section of a balanced scorecard retains the types of metrics that have historically been set by companies to evaluate performance. The particular metric used in the scorecard will vary depending on the type of company involved, who is being evaluated, and what is being measured. You’ve learned that ROI, RI, and EVA can be used to evaluate performance. There are other financial measures that can be used as well, for example, earnings per share (EPS), revenue growth, sales growth, inventory turnover, and many others. The type of financial measures used should capture the components of the decision-making tasks of the person being evaluated. Financial measures can be very broad and general, such as sales growth, or they can be more specific, such as seat revenue. Looking back at the Scrumptious Sweets example, financial measures could include baked goods revenue growth, drink revenue growth, and product cost containment.

Internal Business Perspective

A successful company should operate like a well-tuned machine. This requires that the company monitor its internal operations and evaluate them to ensure they are meeting the strategic goals of the corporation. There are many variables that could be used as internal business measures, including number of defects produced, machine downtime, transaction efficiency, and number of products completed per day per employee, or more refined measures, such as percent of time planes are on the ground, or ensuring air tanks are well stocked for a scuba diving business. For Scrumptious Sweets, internal measures could include time between production and sale of the baked goods or amount of waste.

Customer Perspectives

All businesses have customers or clients—a business will cease to operate without them—thus, it is important for a company to measure how well it is doing with respect to customers. Examples of common variables that could be measured include customer satisfaction, number of repeat customers, number of new customers, number of new customers from customer referrals, and market share. Variables that are more specific to a particular business include factors such as being ranked first in the industry by customers and providing a safe diving environment for scuba diving. Customer measures for Scrumptious Sweets might include customer loyalty, customer satisfaction, and number of new customers.

Learning and Growth

The business environment is a very dynamic one and requires a company to constantly evolve in order to survive, let alone grow. To reach strategic targets such as increased market share, management must focus on ways to grow the company. The learning and growth measures are a means to assess how the employees and management are working together to grow the company and to help the employees grow within the company. Examples of measures in this category include the number of employee suggestions that are adopted, turnover rates, hours of employee training, scope of process improvements, and number of new products. Scrumptious Sweets may use learning and growth measures such as hours of customer service training and hours on workforce relationship training.

Combining the Four Components of a Balanced Scorecard

Balanced scorecards can be created for any type of business and can be used at any level of the organization. An effective and successful balanced scorecard will start with the strategic plan or goals of the organization. Those goals are then restated based on the level of the organization to which the balanced scorecard pertains. A balanced scorecard for an entire organization will be broader and more general in terms of goals and measures than a balanced scorecard designed for a division manager. Balanced scorecards can even be created at the individual employee level either as an evaluation mechanism or as a means for the employee to set and monitor individual goals. Once the strategic goals of the organization are stated for the appropriate level for which the balanced scorecard is being created, then the measures for each of the categories of the balanced scorecard should be defined, being sure to consider the areas over which the division or individual does or does not have control. In addition, the variables have to be obtainable and measurable. Last, the measures must be useful, meaning that what is actually being measured must be informative, and there must be a basis of comparison—either company standards or individual targets. Using both quantitative and nonquantitative performance measures, along with long- and short-term measurements, can be very beneficial, as they can serve to motivate an employee while providing a clear framework of how that employee fits into the company’s strategic plan.

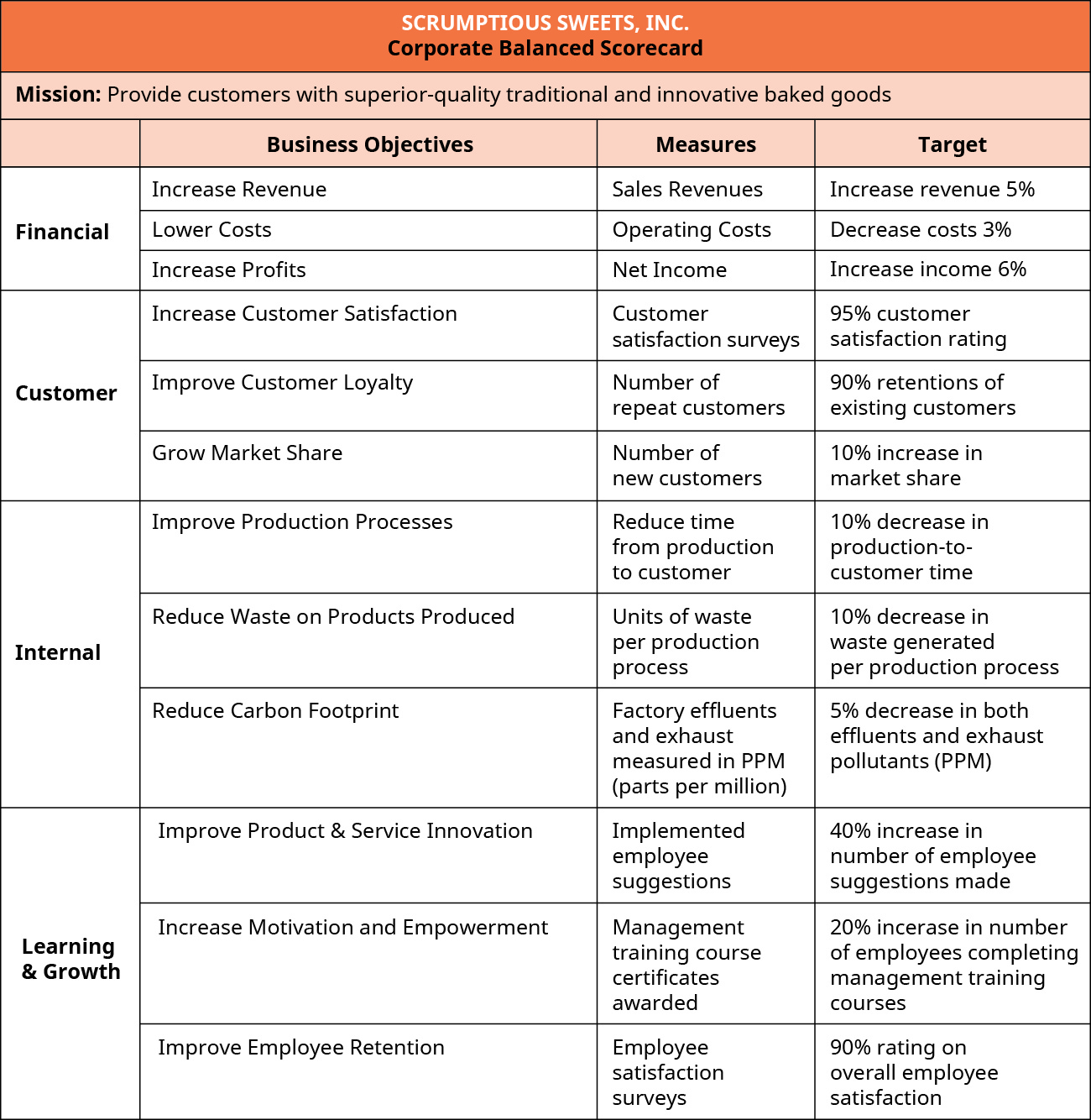

As an example, let’s examine several balanced scorecards for Scrumptious Sweets. First, (Figure) shows an overall organizational balanced scorecard, the broadest and most general balanced scorecard.

Notice that this scorecard starts with the overall corporate mission. It then contains very broad goals and measures in each of the four categories: financial, customer, internal, and learning and growth. In this scorecard, there are three general goals for each of these four categories. For example, the goals related to customers are to improve customer satisfaction, improve customer loyalty, and increase market share. For each of the goals, there is a general measure that will be used to assess if the goal has been met. In this example, the goal to improve customer satisfaction will be assessed using customer satisfaction surveys. But remember, measures are only useful as a management tool if there is a target to work toward. In this case, the goal is to achieve an overall 95% customer satisfaction rating. Obviously, the goals on this scorecard and the associated measures seem almost vague due to their general nature. However, these goals match with the overall corporate strategy and provide guidance for management at lower levels to begin dissecting these goals to more specific ones that pertain to their particular area or division. This allows them to create more detailed balanced scorecards that will allow them to help meet the overall corporate goals laid out in the corporate scorecard. (Figure) shows how the corporate balanced scorecard previously presented could be further detailed for the manager of the brownie division.

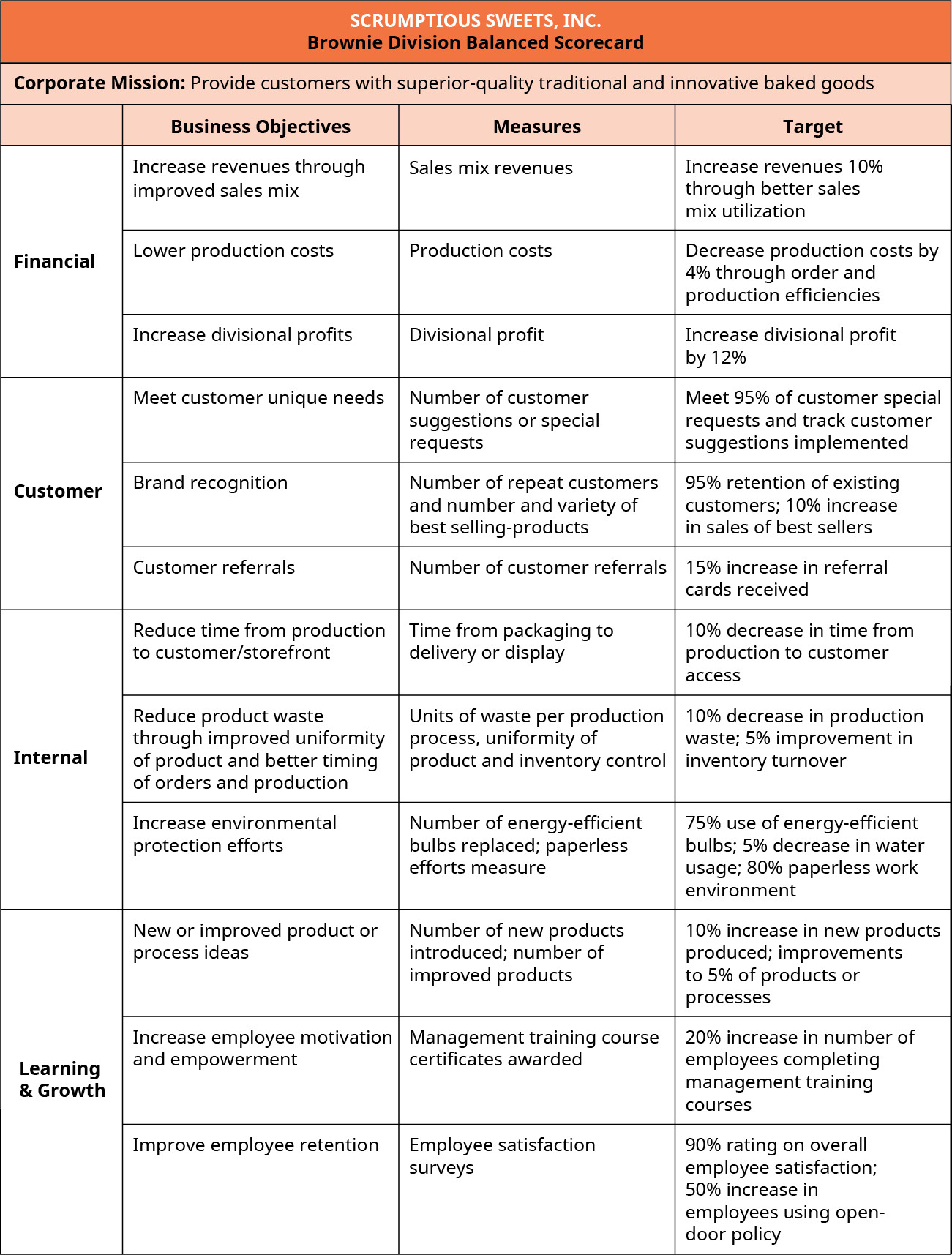

As you can see from the balanced scorecard for the brownie division, the same corporate mission is included, as are the same four categories; however, the divisional goals are more specific, as are the measures and the targets. For example, related to the overall corporate goal to increase customer satisfaction, the divisional goal is to meet customers’ unique needs. The division will assess how well they are accomplishing this goal by tracking the number of customer suggestions and customer special requests, such as when a customer requests a special flavor of brownie not normally produced by the brownie division. The target set by the management of the brownie division is to meet 95% of customer special requests and to track the number of customer suggestions that are implemented by the division. The idea is that if the division is meeting customer needs and requests, this will result in high customer satisfaction, which is an overriding corporate goal. The success of the division will be based on each employee doing his or her best at his or her specific job. Therefore, it is useful to see how the balanced scorecard can be used at an individual employee level. (Figure) shows a balanced scorecard for the brownie division’s employees who work in the front end or store portion of the division.

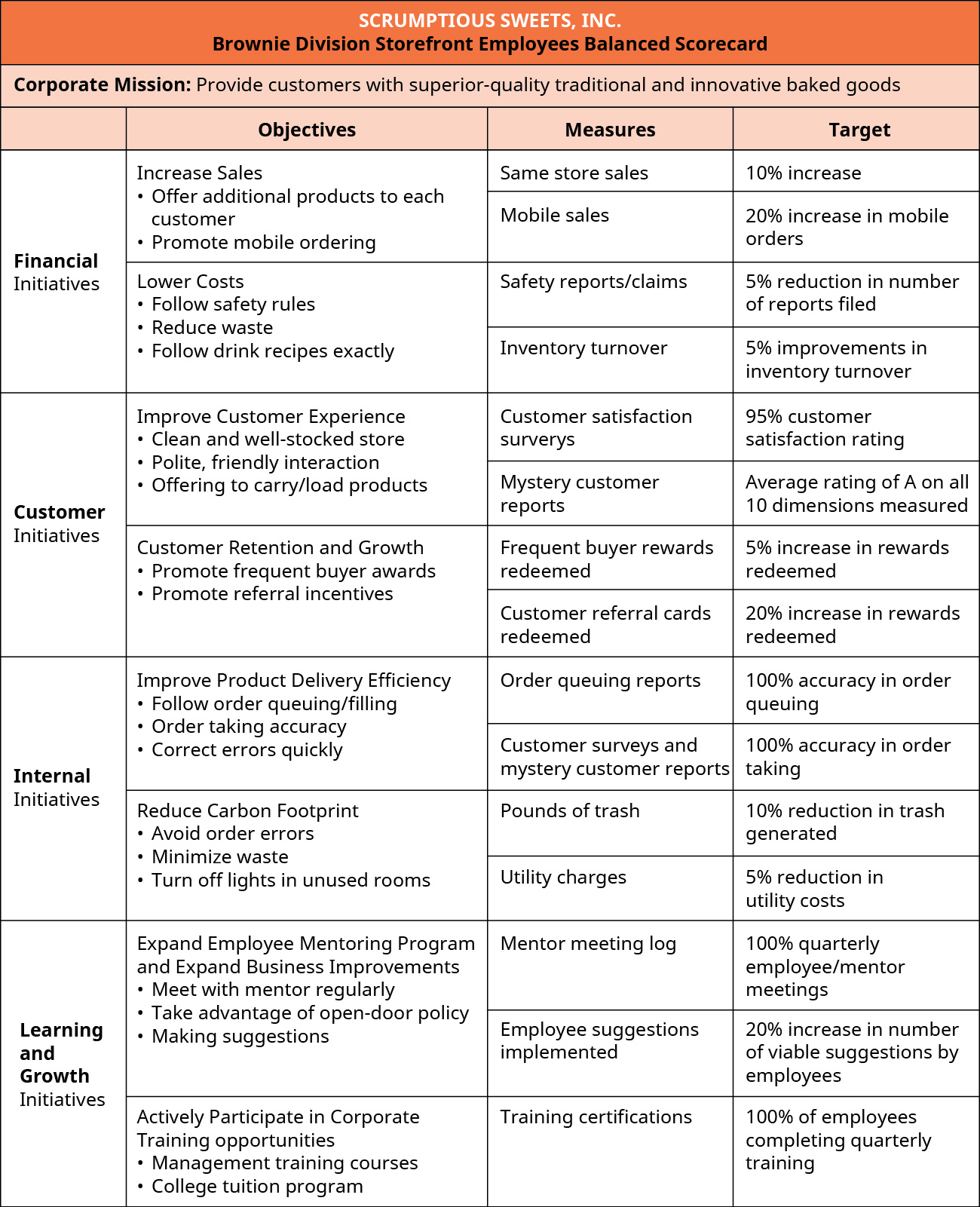

In this balanced scorecard the same categories are used, but there is more detail about each of the business objectives, and each objective has more refined measures than the prior two scorecards. Again in the customer category, one of the objectives of the storefront employees is to improve the customer experience. Notice that there are three initiatives listed to help drive this goal. The measures that would be used to evaluate the success of these initiatives as well as their specific targets are detailed. Again, the idea is that if the employees who work in the store portion of the brownie division make the customer experience great, this will translate into high scores on the customer satisfaction surveys and help the company meet its overriding goal to increase customer satisfaction. In order to ensure that this occurs, the specific goals and metrics are created. As previously expressed, it is best if these objectives, measures, and targets are determined by a process that includes management and the employees. Without employee input, employees may feel resentful of targets over which they had no input. But, the employees alone cannot set their own goals and targets, as there could be a tendency to set easy targets, or the employee may not be aware of how his or her efforts affect the division and overall corporation. Thus, a collaborative approach is best in creating balanced scorecards.

The three scorecards presented show that the process of creating appropriate and viable scorecards can be quite complicated and challenging. Determining the appropriate qualitative and quantitative measures can be a daunting process, but the results can be extremely beneficial. The scorecards can be useful tools at all levels of the organization if they are adequately thought out and if there is buy-in at all levels being evaluated by a scorecard. Next, we’ll consider how the use of the balanced scorecard and performance measures are not mutually exclusive and can work well together.

CONTINUING APPLICATION

Let’s revisit Gearhead Outfitters in the context of their operating results, internal processes, growth, and customer satisfaction. Recall that the company was founded as a single store in 1997 and grew to multiple locations mainly in the southern United States. How did Gearhead get there? How did the company gather information to make expansion decisions? Now that Gearhead has expanded, should it keep all current locations open? Is the company meeting the desires of its customers?

Questions such as these are addressed through performance measures detailed in a balanced scorecard. Financial metrics such as return on investment and residual income give Gearhead information on whether or not dollars invested have translated into additional income, and if current income can support needed cash flow for current and future operations. While financial measures are important, they are only one aspect of evaluating the effectiveness of a company’s strategy. Value provided to customers should also be considered, as well as the success of internal processes, and whether or not the company adequately provides growth opportunities for employees. Sales from new products, employee turnover, and customer satisfaction surveys can also provide valuable data for measuring success. The idea of a balanced scorecard is to give a business both financial and nonfinancial information to use in its strategic decisions.

The Our Story page of Gearhead’s website reads: “Gearhead Outfitters exists to create a positive shopping experience for our guests. Gearhead is known for its relaxed environment, specialized inventory and customer service for those pursuing an active lifestyle. True to our local roots, we employ local residents of each city we operate in, support local organizations, and strive to build relationships within our communities.”3

Given how Gearhead describes itself, and the performance measures discussed previously, what other information might the company want to gather for its balanced scorecard?

Final Summary of Quantitative and Quantitative Performance Measurement Tools

As the business environment changes, one thing stays the same: businesses want to be successful, to be profitable, and to meet their strategic goals. With these changes in the business environment come more varied responsibilities placed on managers. These changes occur due to an increased use of technology along with ever-increasing globalization. It is very important that an organization can appropriately measure whether employees are meeting these various responsibilities and reward them accordingly.

You’ve learned about some common performance measures such as ROI, RI, EVA, and the balanced scorecard. The more accurately and efficiently a company can monitor and measure its decision-making processes at all levels, the more quickly it can respond to change or problems, and the more likely the company will be able to meet its strategic goals. Most companies will use some combination of the quantitative and nonquantitative measures described. ROI, RI, and EVA are typically used to evaluate specific projects, but ROI is sometimes used as a divisional measure. These measures are all quantitative measures. The balanced scorecard not only has quantitative measures but adds qualitative measures to address more of the goals of the organization. The combination of these different types of quantitative and qualitative measures—project-specific measures, employee-level measures, divisional measures, and corporate measures—enables an organization to more adequately assess how it is progressing toward meeting short- and long-term goals. Remember, the best performance measurement system will contain multiple measures and consist of both quantitative and qualitative factors, which allows for better assessment of managers and better results for the corporation.

THINK IT THROUGH

For each of the following businesses, what are four nonfinancial measures that might be useful for helping management evaluate the success of its strategies?

- Grocery store

- Hospital

- Auto manufacturer

- Law office

- Coffee shop

- Movie theater

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Concepts and Summary

- Balanced scorecards use both financial and nonfinancial measures to evaluate employees.

- The four categories of a balanced scorecard are financial perspective, internal business perspective, customer perspective, and learning and growth perspective.

- Financial perspective measures are usually traditional measures, based on financial statement information such as EPS or ROI.

- Internal business perspective measures are those that evaluate management’s operational goals, such as quality control or on-time production.

- Customer perspective measures are those that evaluate how the customer perceives the business and how the business interacts with customers.

- Learning and growth perspective measures are those that evaluate how effectively the company is growing by innovating and creating value. This is often done through employee training.

- Well-designed balanced scorecards can be very effective at goal congruence through the utilization of both financial and nonfinancial measures.

- 1 Alistair Craven. An Interview with Robert Kaplan & David Norton (Emerald Publishing, 2008). http://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/learning/management_thinking/interviews/kaplan_norton.htm

- 2 Paul Arveson. The Ethics Perspective (Balanced Scorecard Institute, Strategy Management Group, 2002). https://www.balancedscorecard.org/The-Ethics-Perspective

- 3 Gearhead Outfitters. “Our Story.” https://www.gearheadoutfitters.com/about-us/our-story/

- 4 https://www.vinfen.org

Glossary

- balanced scorecard

- tool used to evaluate performance using qualitative and nonqualitative measures

- qualitative factor

- component of a decision-making process that cannot be measured numerically

- quantitative factor

- component of a decision-making process that can be measured numerically

- stakeholder

- someone affected by decisions made by a company; may include an investor, creditor, employee, manager, regulator, customer, supplier, and layperson

- stockholder

- owner of stock, or shares, in a business

Adapted from Principles of Accounting, Volume 2: Managerial Accounting (c) 2019 by Open Stax. The textbook content was produced by Open Stax and is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-managerial-accounting

tool used to evaluate performance using qualitative and nonqualitative measures

component of a decision-making process that can be measured numerically

component of a decision-making process that cannot be measured numerically

owner of stock, or shares, in a business

person or group with an interest or concern in some aspect of the organization OR someone affected by decisions made by a company; may include an investor, creditor, employee, manager, regulator, customer, supplier, and layperson