LO 4.6 Define, Explain, and Provide Examples of Current and Noncurrent Assets, Current and Noncurrent Liabilities

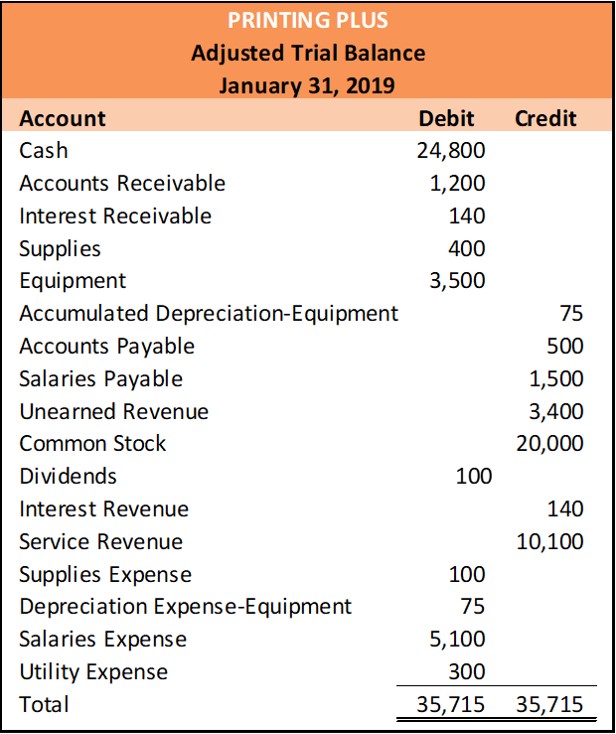

In the section Prepare Financial Statements Using the Adjusted Trial Balance you used the adjusted trial balance to prepare financial statements, including an income statement, statement of retained earnings, and balance sheet, for Printing Plus. The balance sheet was prepared using the report form and was not classified. In this section, we will continue to use Printing Plus’s Adjusted Trial Balance as of January 31, 2019, but this time we will prepare a classified balance sheet using the account form. You will see that total assets, total liabilities and total equity remain the same, but the layout and subtotals will be different. Before we can prepare a classified balance sheet, you need to know about the classifications we find useful for assets and liabilities.

In accounting, we classify assets based on whether or not the asset will be converted to cash or consumed within a certain period of time, generally one year. If the asset will be converted to cash or consumed in one year or less, we classify the asset as a current asset. If the asset will not be converted to cash or consumed within a year, we classify the asset as a noncurrent asset. Take a look at Printing Plus’s Adjusted Trial Balance and focus on its assets. Which of the assets would Printing Plus be likely to receive cash for, or use up within one year?

Since Cash is already cash, it is always considered to be a current asset. Generally, we would expect to receive cash from our Accounts Receivable within 30 to 60 days, so Accounts Receivable is a current asset. As long as we expect to receive our interest within a year, Interest Receivable is a current asset. Supplies is a little different in that we do not expect to receive cash for our supplies at any time. But we do expect to consume or use up our supplies, generally within a year. So Supplies is a current asset. Then we come to Equipment. We assume that Printing Plus plans to use the equipment over multiple years, so Equipment is a noncurrent asset. (The Accumulated Depreciation account will move with the Equipment account into the balance sheet.)

One more thing about asset classifications — sometimes we find it useful to organize noncurrent assets into groups, including Plant and Equipment, Investments, and Intangible Assets. The Plant and Equipment category includes vehicles, land, buildings, and equipment that are used in the business’s operations. Investments can include stocks or bonds (issued by other corporations) or land or buildings held for investment purposes, not for use in operations. An intangible asset is one that lacks physical substance—it cannot be touched or moved. Examples of intangible assets include trademarks, copyrights, patents and something called goodwill.

Similar to the accounting for assets, liabilities are classified based on the time frame in which the liabilities are expected to be paid or settled. A liability that will be paid or settled in one year or less (generally) is classified as a current liability, while a liability that is expected to be paid in more than one year is classified as a noncurrent liability.

Which of Printing Plus’s liabilities will require payment or settlement within a year? Accounts payable, amounts the company owes to suppliers, are almost always due within 30 to 60 days. So Accounts Payable is a current liability. Salaries Payable is also a current liability, because the salaries will have to be paid on the next pay day. Unearned revenue (cash the company received from a client before the company provided and services) is usually a current liability, since the services are usually due to be provided within a year. So Printing Plus has no noncurrent liabilities, but some examples of amounts the company might owe, but not have to pay for more than one year, are notes payable and bonds payable with maturity dates that extend beyond a year.

Why Does Current versus Noncurrent Matter?

At this point, let’s take a break and explore why the distinction between current and noncurrent assets and liabilities matters. It is a good question because, on the surface, it does not seem to be important to make such a distinction. After all, assets are things owned or controlled by the organization, and liabilities are amounts owed by the organization; listing those amounts in the financial statements provides valuable information to stakeholders. But we have to dig a little deeper and remind ourselves that stakeholders are using this information to make decisions. Providing the amounts of the assets and liabilities answers the “what” question for stakeholders (that is, it tells stakeholders the value of assets), but it does not answer the “when” question for stakeholders. For example, knowing that an organization has $1,000,000 worth of assets is valuable information, but knowing that $250,000 of those assets are current and will be converted to cash or consumed within one year is more valuable to stakeholders. Likewise, it is helpful to know the company owes $750,000 worth of liabilities, but knowing that $125,000 of those liabilities will need to be paid within one year is even more valuable. In short, the timing of events is of particular interest to stakeholders.

THINK IT THROUGH

When money is borrowed by an individual or family from a bank or other lending institution, the loan is considered a personal or consumer loan. Typically, payments on these types of loans begin shortly after the funds are borrowed. Student loans are a special type of consumer borrowing that has a different structure for repayment of the debt. If you are not familiar with the special repayment arrangement for student loans, do a brief internet search to find out when student loan payments are expected to begin.

Now, assume a college student has two loans—one for a car and one for a student loan. Assume the person gets the flu, misses a week of work at his campus job, and does not get paid for the absence. Which loan would the person be most concerned about paying? Why?

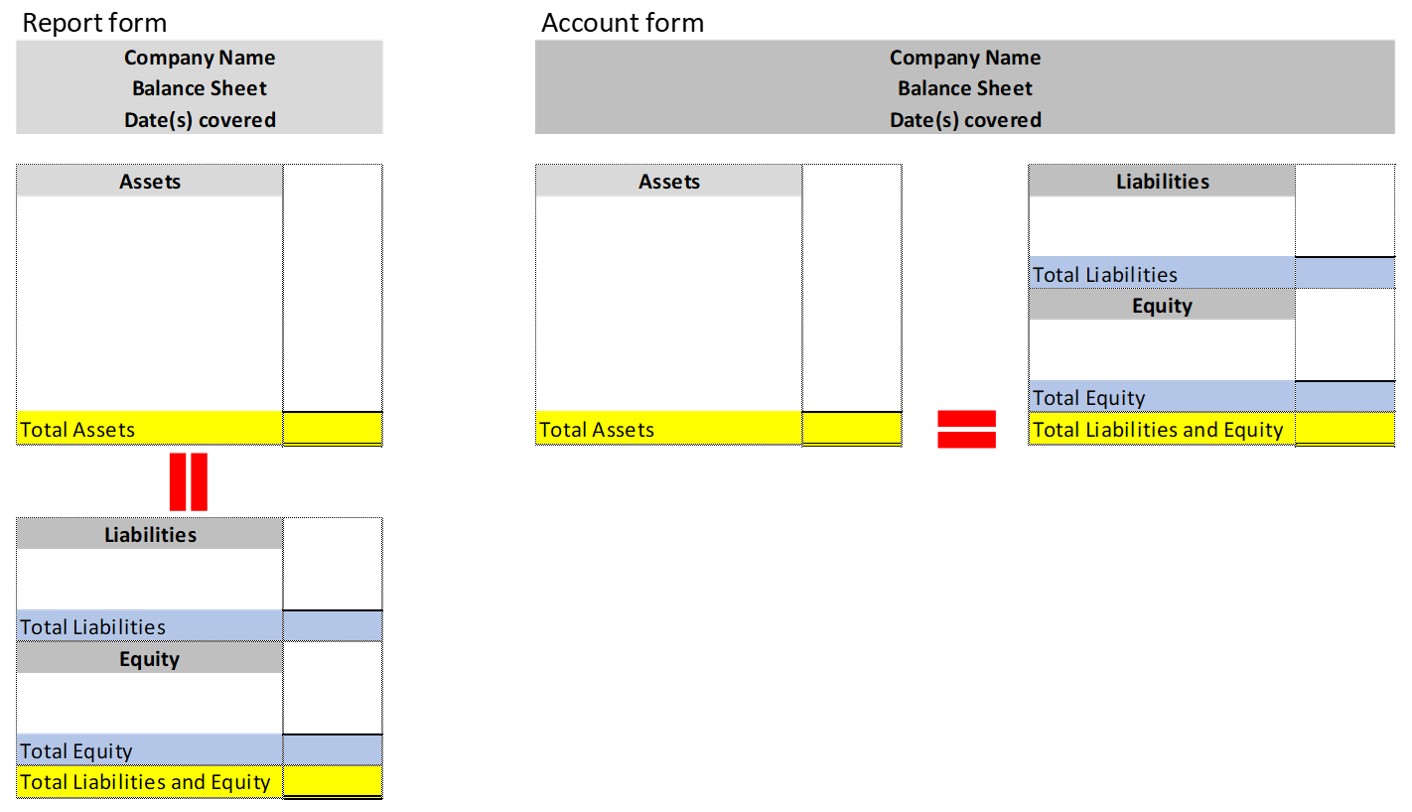

Because the timing of receiving cash and paying cash is critical for businesses, a balance sheet that shows both current assets and current liabilities is useful. When a balance sheet subdivides assets and liabilities into current and noncurrent sections, it’s called a classified balance sheet. We will prepare a classified balance sheet for Printing Plus, but we need to clarify one more point first. Any balance sheet, whether classified or not, can be laid out in either of two ways — we can use either the report form or the account form. Both forms display the accounting equation (assets = liabilities + equity). But the report form displays the equation vertically, whereas the account form displays the equation horizontally. Here’s an illustration of the two forms:

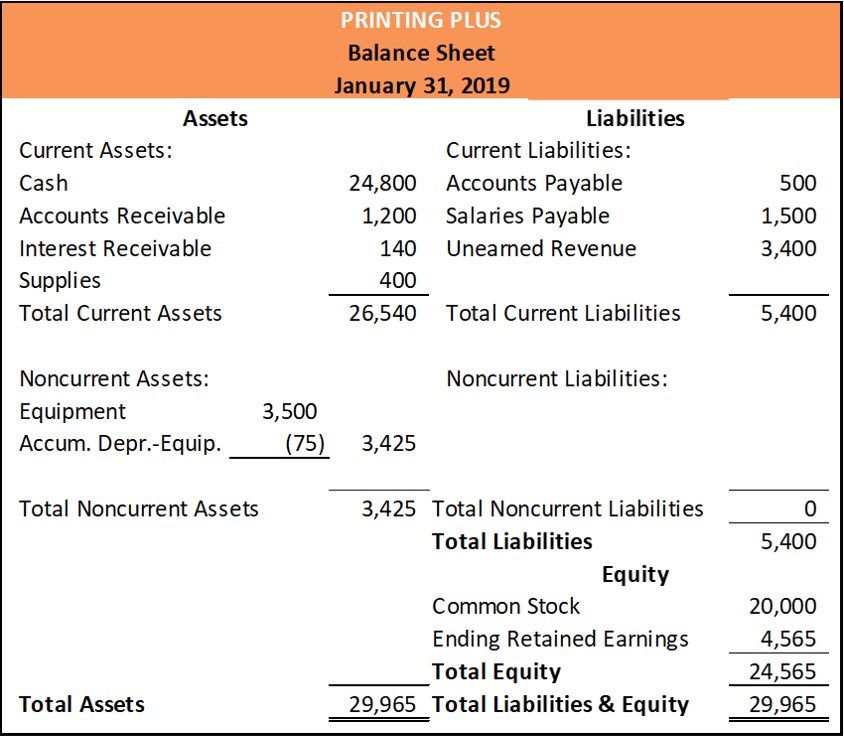

Regardless of which form you use, total assets must equal total liabilities and equity. You have already seen the (unclassified) report form of Printing Plus’s balance sheet. Now we’ll show you the classified, account form of the balance sheet:

Notice that Total Assets is still $29,965, Total Liabilities is still $5,400, and Total Equity is still $24,565, just like we saw in the report form, unclassified balance sheet. But now we can easily compare the company’s current assets, $26,540, to it’s current liabilities, $5,400 and surmise that Printing Plus should be able to pay or settle its current liabilities without difficulty. When we compare current assets to current liabilities, we are evaluating a company’s liquidity.

Liquidity Ratios

In addition to reviewing the financial statements in order to make decisions, owners and other stakeholders may also utilize financial ratios to assess the financial health of the organization. While a more in-depth discussion of financial ratios occurs in Appendix A: Financial Statement Analysis, here we introduce liquidity ratios, a common, easy, and useful way to analyze the financial statements.

Liquidity refers to the business’s ability to convert assets into cash in order to meet short-term cash needs. Examples of the most liquid assets include accounts receivable and inventory for merchandising or manufacturing businesses. The reason these are among the most liquid assets is that these assets will be turned into cash more quickly than land or buildings, for example. Accounts receivable represents goods or services that have already been sold and will typically be collected within thirty to forty-five days. Inventory is less liquid than accounts receivable because the product must first be sold before it generates cash (either through a cash sale or sale on account). Inventory is, however, more liquid than land or buildings because, under most circumstances, it is easier and quicker for a business to find someone to purchase its goods than it is to find a buyer for land or buildings.

Working Capital

The starting point for understanding liquidity ratios is to define working capital—current assets minus current liabilities. Recall that current assets and current liabilities are amounts generally settled in one year or less. Working capital (current assets minus current liabilities) is used to assess the dollar amount of assets a business has available to meet its short-term liabilities. A positive working capital amount is desirable and indicates the business has sufficient current assets to meet short-term obligations (liabilities) and still has financial flexibility. A negative amount is undesirable and indicates the business should pay particular attention to the composition of the current assets (that is, how liquid the current assets are) and to the timing of the current liabilities. It is unlikely that all of the current liabilities will be due at the same time, but the amount of working capital gives stakeholders of both small and large businesses an indication of the firm’s ability to meet its short-term obligations.

One limitation of working capital is that it is a dollar amount, which can be misleading because business sizes vary. Recall from the discussion on materiality that $1,000, for example, is more material to a small business (like an independent local movie theater) than it is to a large business (like a movie theater chain). Using percentages or ratios allows financial statement users to more easily compare small and large businesses.

Current Ratio

The current ratio is closely related to working capital; it represents the current assets divided by current liabilities. The current ratio utilizes the same amounts as working capital (current assets and current liabilities) but presents the amount in ratio, rather than dollar, form. That is, the current ratio is defined as current assets/current liabilities. The interpretation of the current ratio is similar to working capital. A ratio of greater than one indicates that the firm has the ability to meet short-term obligations with a buffer, while a ratio of less than one indicates that the firm should pay close attention to the composition of its current assets as well as the timing of the current liabilities.

Glossary

- classified balance sheet

- categories or groupings used to record transactions and prepare financial statements

- current ratio

- current assets divided by current liabilities; used to determine a company’s liquidity (ability to meet short-term obligations)

- liquidity

- ability to convert assets into cash in order to meet primarily short-term cash needs or emergencies

- working capital

- current assets less current liabilities; sometimes used as a measure of liquidity

Adapted from Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting (c) 2010 by Open Stax. The textbook content was produced by Open Stax and is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-financial-accounting

a balance sheet that organizes assets into current and noncurrent sections and liabilities into current and noncurrent sections

ability to convert assets into cash in order to meet primarily short-term cash needs or emergencies

current assets less current liabilities; sometimes used as a measure of liquidity

current assets divided by current liabilities; used to determine a company’s liquidity (ability to meet short-term obligations)