LO 4.1 Explain the Concepts and Guidelines Affecting Adjusting Entries

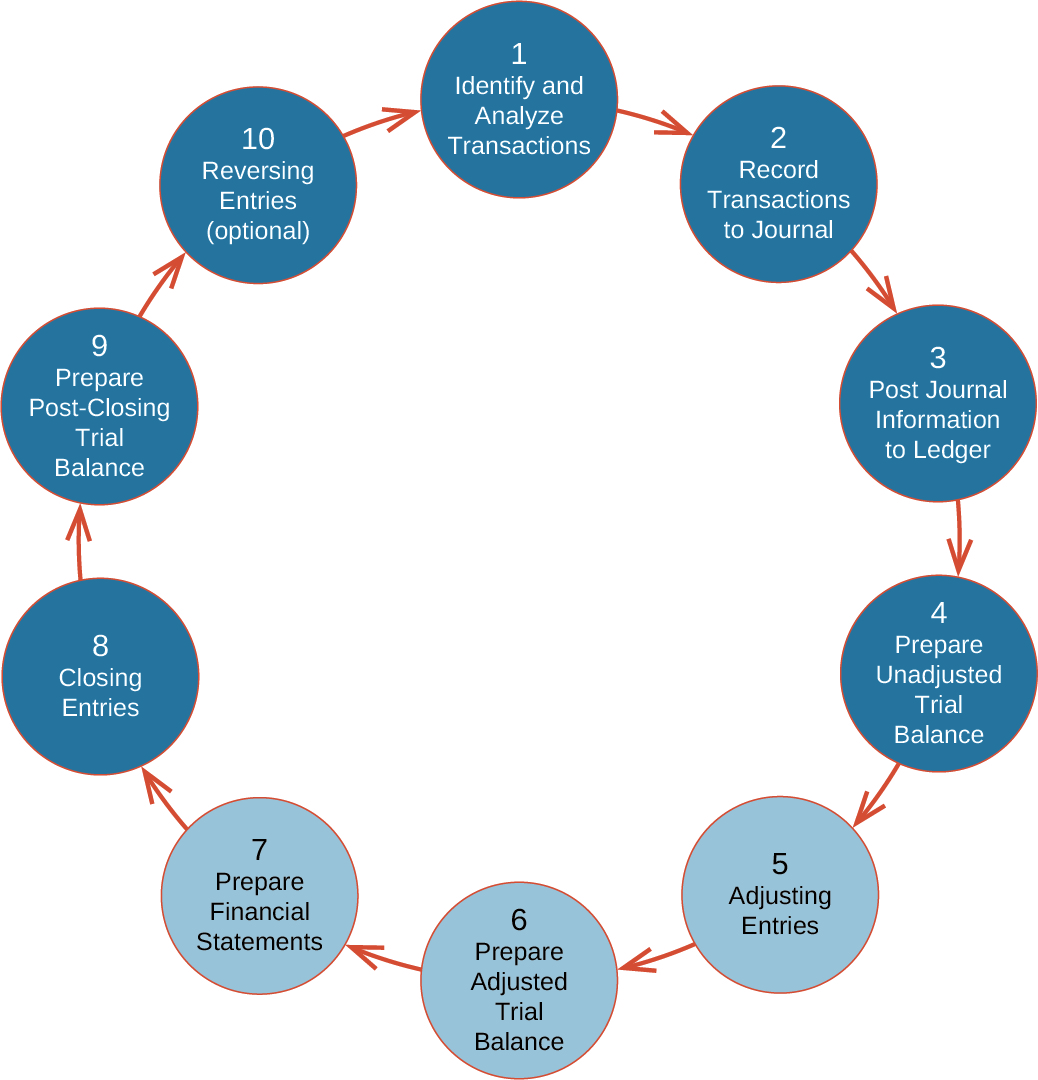

Analyzing and Recording Transactions was the first of three consecutive chapters covering the steps in the accounting cycle.

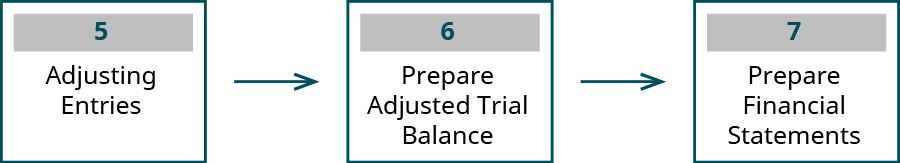

In Analyzing and Recording Transactions, we discussed the first four steps in the accounting cycle: identify and analyze transactions, record transactions to a journal, post journal information to the general ledger, and prepare an (unadjusted) trial balance. This chapter examines the next three steps in the cycle: record adjusting entries (journalizing and posting), prepare an adjusted trial balance, and prepare the financial statements.

As we progress through these steps, you learn why the trial balance in this phase of the accounting cycle is referred to as an “adjusted” trial balance. We also discuss the purpose of adjusting entries and the accounting concepts supporting their need. One of the first concepts we discuss is accrual accounting.

Accrual Accounting

Public companies reporting their financial positions use either US generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), as allowed under the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations. Also, companies, public or private, using US GAAP or IFRS prepare their financial statements using the rules of accrual accounting. Accrual basis accounting prescribes that revenues and expenses must be recorded in the accounting period in which they were earned or incurred, no matter when cash receipts or payments occur. It is because of accrual accounting that we have the revenue recognition principle and the expense recognition principle (also known as the matching principle).

The accrual method is considered to better match revenues and expenses and standardizes reporting information for comparability purposes. Having comparable information is important to external users of information trying to make investment or lending decisions, and to internal users trying to make decisions about company performance, budgeting, and growth strategies.

Some nonpublic companies may choose to use cash basis accounting rather than accrual basis accounting to report financial information. Recall from Introduction to Financial Statements that cash basis accounting is a method of accounting in which transactions are not recorded in the financial statements until there is an exchange of cash. Cash basis accounting sometimes delays or accelerates revenue and expense reporting until cash receipts or outlays occur. With this method, cash flows are used to measure business performance in a given period and can be simpler to track than accrual basis accounting.

There are several other accounting methods or concepts that accountants will sometimes apply. The first is modified accrual accounting, which is commonly used in governmental accounting and merges accrual basis and cash basis accounting. The second is tax basis accounting that is used in establishing the tax effects of transactions in determining the tax liability of an organization.

One fundamental concept to consider related to the accounting cycle—and to accrual accounting in particular—is the idea of the accounting period.

The Accounting Period

As we discussed, accrual accounting requires companies to report revenues and expenses in the accounting period in which they were earned or incurred. An accounting period breaks down company financial information into specific time spans, and can cover a month, a quarter, a half-year, or a full year. Public companies governed by GAAP are required to present quarterly (three-month) accounting period financial statements called 10-Qs. However, most public and private companies keep monthly, quarterly, and yearly (annual) period information. This is useful to users needing up-to-date financial data to make decisions about company investment and growth. When the company keeps yearly information, the year could be based on a fiscal or calendar year. This is explained shortly.

CONTINUING APPLICATION AT WORK

In every industry, adjustment entries are made at the end of the period to ensure revenue matches expenses. Companies with an online presence need to account for items sold that have not yet been shipped or are in the process of reaching the end user. But what about the grocery industry? At first glance, it might seem that no such adjustment entries are necessary. However, grocery stores have adapted to the current retail environment. For example, your local grocery store might provide catering services for a graduation party. If the contract requires the customer to put down a 50% deposit, and occurs near the end of a period, the grocery store will have unearned revenue until it provides the catering service. Once the party occurs, the grocery store needs to make an adjusting entry to reflect that revenue has been earned.

The Fiscal Year and the Calendar Year

A company may choose its yearly reporting period to be based on a calendar or fiscal year. If a company uses a calendar year, it is reporting financial data from January 1 to December 31 of a specific year. This may be useful for businesses needing to coincide with a traditional yearly tax schedule. It can also be easier to track for some businesses without formal reconciliation practices, and for small businesses.

A fiscal year is a twelve-month reporting cycle that can begin in any month and records financial data for that consecutive twelve-month period. For example, a business may choose its fiscal year to begin on April 1, 2019, and end on March 31, 2020. This can be common practice for corporations and may best reflect the operational flow of revenues and expenses for a particular business. In addition to annual reporting, companies often need or choose to report financial statement information in interim periods.

Interim Periods

An interim period is any reporting period shorter than a full year (fiscal or calendar). This can encompass monthly, quarterly, or half-year statements. The information contained on these statements is timelier than waiting for a yearly accounting period to end. The most common interim period is three months, or a quarter. For companies whose common stock is traded on a major stock exchange, meaning these are publicly traded companies, quarterly statements must be filed with the SEC on a Form 10-Q. The companies must file a Form 10-K for their annual statements. As you’ve learned, the SEC is an independent agency of the federal government that provides oversight of public companies to maintain fair representation of company financial activities for investors to make informed decisions.

In order for information to be useful to the user, it must be timely—that is, the user has to get it quickly enough so it is relevant to decision-making. You may recall from Analyzing and Recording Transactions that this is the basis of the time period assumption in accounting. For example, a potential or existing investor wants timely information by which to measure the performance of the company, and to help decide whether to invest, to stay invested, or to sell their stockholdings and invest elsewhere. This requires companies to organize their information and break it down into shorter periods. Internal and external users can then rely on the information that is both timely and relevant to decision-making.

The accounting period a company chooses to use for financial reporting will impact the types of adjustments they may have to make to certain accounts.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

From 2000 through the end of 2001, Bristol-Myers Squibb engaged in “Cookie Jar Accounting,” resulting in $150 million in SEC fines. The company manipulated its accounting to create a false indication of income and growth to create the appearance that it was meeting its own targets and Wall Street analysts’ earnings estimates during the years 2000 and 2001. The SEC describes some of what occurred:

Bristol-Myers inflated its results primarily by (1) stuffing its distribution channels with excess inventory near the end of every quarter in amounts sufficient to meet its targets by making pharmaceutical sales to its wholesalers ahead of demand; and (2) improperly recognizing $1.5 billion in revenue from such pharmaceutical sales to its two biggest wholesalers. In connection with the $1.5 billion in revenue, Bristol-Myers covered these wholesalers’ carrying costs and guaranteed them a return on investment until they sold the products. When Bristol-Myers recognized the $1.5 billion in revenue upon shipment, it did so contrary to generally accepted accounting principles.1

In addition to the improper distribution of product to manipulate earnings numbers, which was not enough to meet earnings targets, the company improperly used divestiture reserve funds (a “cookie jar” fund that is funded by the sale of assets such as product lines or divisions) to meet those targets. In this circumstance, earnings management was considered illegal, costing the company millions of dollars in fines.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Concepts and Summary

- The next three steps in the accounting cycle are adjusting entries (journalizing and posting), preparing an adjusted trial balance, and preparing the financial statements. These steps consider end-of-period transactions and their impact on financial statements.

- Accrual basis accounting is used by US GAAP or IFRS-governed companies, and it requires revenues and expenses to be recorded in the accounting period in which they occur, not necessarily where an associated cash event happened. This is unlike cash basis accounting that will delay reporting revenues and expenses until a cash event occurs.

- Companies need timely and consistent financial information presented for users to consider in their decision-making. Accounting periods help companies do this by breaking down information into months, quarters, half-years, and full years.

- A calendar year considers financial information for a company for the time period of January 1 to December 31 on a specific year. A fiscal year is any twelve-month reporting cycle not beginning on January 1 and ending on December 31.

- An interim period is any reporting period that does not cover a full year. This can be useful when needing timely information for users making financial decisions.

Glossary

- accounting period

- breaks down company financial information into specific time spans and can cover a month, quarter, half-year, or full year

- accrual basis accounting

- accounting system in which revenue is recorded or recognized when earned yet not necessarily received, and in which expenses are recorded when legally incurred and not necessarily when paid

- calendar year

- reports financial data from January 1 to December 31 of a specific year

- fiscal year

- twelve-month reporting cycle that can begin in any month, and records financial data for that twelve-month consecutive period

- interim period

- any reporting period shorter than a full year (fiscal or calendar)

- modified accrual accounting

- commonly used in governmental accounting and combines accrual basis and cash basis accounting

Adapted from Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting (c) 2010 by Open Stax. The textbook content was produced by Open Stax and is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-financial-accounting

accounting system in which revenue is recorded or recognized when earned yet not necessarily received, and in which expenses are recorded when legally incurred and not necessarily when paid

commonly used in governmental accounting and combines accrual basis and cash basis accounting

breaks down company financial information into specific time spans and can cover a month, quarter, half-year, or full year

reports financial data from January 1 to December 31 of a specific year

twelve-month reporting cycle that can begin in any month, and records financial data for that twelve-month consecutive period

any reporting period shorter than a full year (fiscal or calendar)