LO 13.4 Special Topics Related to Long-Term Liabilities

Here we will address some special topics related to long-term liabilities.

Brief Comparison between Equity and Debt Financing

Although we briefly addressed equity versus debt financing in Explain the Pricing of Long-Term Liabilities, we will now review the two options. Let’s consider Maria, who wants to buy a business. The venture is for sale for $1 million, but she only has $200,000. What are her options? In this situation, a business owner can use debt financing by borrowing money or equity financing by selling part of the company, or she can use a combination of both.

Debt financing means borrowing money that will be repaid on a specific date in the future. Many companies have started by incurring debt. To decide whether this is a viable option, the owners need to determine whether they can afford the monthly payments to repay the debt. One positive to this scenario is that interest paid on the debt is tax deductible and can lower the company’s tax liability. On the other hand, businesses can struggle to make these payments every month, especially as they are starting out.

With equity financing, a business owner sells part of the business to obtain money to finance business operations. With this type of financing, the original owner gives up some portion of ownership in the company in return for cash. In Maria’s case, partners would supplement her $200,000 and would then own a share of the business. Each partner’s share is based on their financial or other contributions.

If a business owner forms a corporation, each owner will receive shares of stock. Typically, those making the largest financial investment have the largest say in decisions about business operations. The issuance of dividends should also be considered in this set-up. Paying dividends to shareholders is not tax deductible, but dividend payments are also not required. Additionally, a company does not have to buy back any stock it sells.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Many start-ups and small companies with just one or two owners struggle to obtain the cash to run their operations. Owners may want to use lending, or debt financing, to obtain the money to run operations, but have to turn to investors, or equity financing. Ethical and legal obligations to investors are typically greater than ethical and legal obligations to lenders. This is because a company’s owners have an ethical and legal responsibility to take investors’ interests into account when making business decisions, even if the decision is not in the founding owners’ best interest. The primary obligation to lenders, however, is only to pay back the money borrowed with interest. When determining which type of financing is appropriate for a business operation, the different ethical and legal obligations between having lenders or investors need to be considered.1

Equity Financing

For a corporation, equity financing involves trading or selling shares of stock in the business to raise funds to run the business. For a sole proprietorship, selling part of the business means it is no longer a sole proprietorship: the subsequent transaction could create either a corporation or partnership. The owners would choose which of the two to create. Equity means ownership. However, business owners can be creative in selling interest in their venture. For example, Maria might sell interest in the building housing her candy store and retain all revenues for herself, or she may decide to share interest in the operations (sales revenues) and retain sole ownership of the building.

The main benefit of financing with equity is that the business owner is not required to pay back the invested funds, so revenue can be re-invested in the company’s growth. Companies funded this way are also more likely to succeed through their initial years. The Small Business Administration suggests a new business should have access to enough cash to operate for six months without having to borrow. The disadvantages of this funding method are that someone else owns part of the business and, depending on the arrangement, may have ideas that conflict with the original owner’s ideas but that cannot be disregarded.

The following characteristics are specific to equity financing:

- No required payment to owners or shareholders; dividends or other distributions are optional. Stock owners typically invest in stocks for two reasons: the dividends that many stocks pay or the appreciation in the market value of the stocks. For example, a stock holder might buy Walmart stock for $100 per share with the expectation of selling it for much more than $100 per share at some point in the future.

- Ownership interest held by the original or current owners can be diluted by issuing additional new shares of common stock.

- Unlike bonds that mature, common stocks do not have a definite life. To convert the stock to cash, some of the shares must be sold.

- In the past, common stocks were typically sold in even 100-share lots at a given market price per share. However, with Internet brokerages today, investors can buy any particular quantity they want.

Debt Financing

As you have learned, debt is an obligation to pay back an amount of money at some point in the future. Generally, a term of less than one year is considered short-term, and a term of one year or longer is considered long-term. Borrowing money for college or a car with a promise to pay back the amount to the lender generates debt. Formal debt involves a signed written document with a due date, an interest rate, and the amount of the loan. A student loan is an example of a formal debt.

The following characteristics are specific to debt financing:

- The company is required to make timely interest payments to the holders of the bonds or notes payable.

- The interest in cash that is to be paid by the company is generally locked in at the agreed-upon rate, and thus the same dollar payments will be made over the life of the bond. Virtually all bonds will have a maturity point. When the bond matures, the maturity value, which was the same as the contract or issuance value, is paid to whoever owns the bond.

- The interest paid is deductible on the company’s income tax return.

- Bonds or notes payable do not dilute the company’s ownership interest. The holders of the long-term liabilities do not have an ownership interest.

- Bonds are typically sold in $1,000 increments.

CONCEPTS IN PRACTICE

Businesses sometimes offer lines of credit (short-term debt) to their customers. For example, Wilson Sporting Goods offers open credit to tennis clubs around the country. When the club needs more tennis balls, a club manager calls Wilson and says, “I’d like to order some tennis balls.” The person at Wilson says, “What’s your account number,” and takes the order. Wilson does not ask the manager to sign a note but does expect to be paid back. If the club does not pay within 120 days, Wilson will not let them order more items until the bill is paid. Ordering on open credit makes transactions simpler for the club and for Wilson, since there is not a need to formalize every order. But collecting on the amount might be difficult for Wilson if the club delays payment. For this reason, typically customers must fill out applications, or have a history with the vendor to go on open credit.

Effect of Interest Points and Loan Term in Years on a Loan

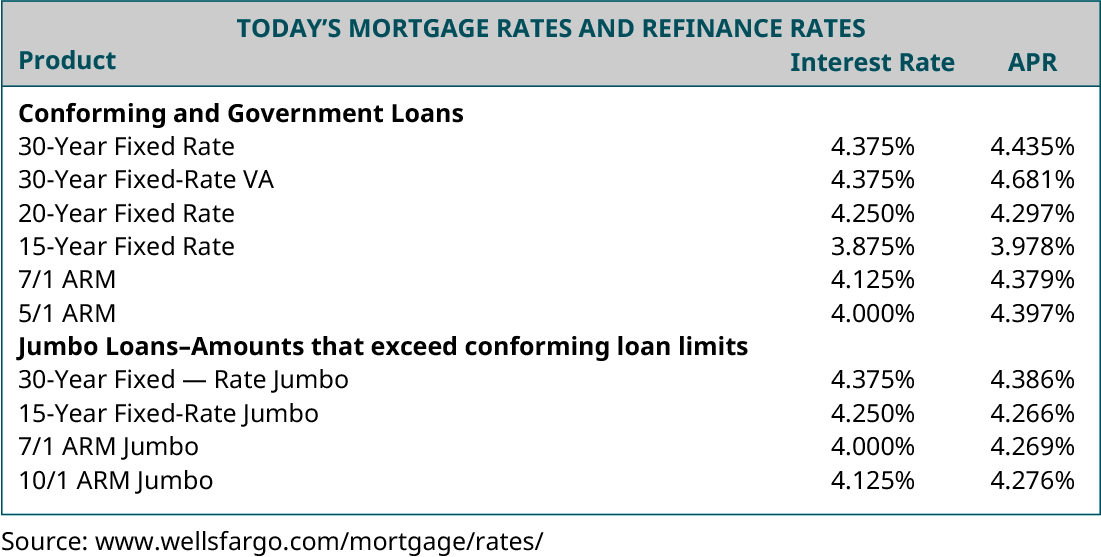

A mortgage loan is typically a long-term loan initiated by a potential home buyer through a mortgage lender. These lenders can be banks and other financial institutions or specialized mortgage lenders. (Figure) shows some examples of the major categories of loans. The table demonstrates some interesting characteristics of home loans.

The first characteristic is that loans can be classified into several categories. One category is the length of the loan, usually 15 years, 20 years, or 30 years. Some mortgages lock in a fixed interest rate for the life of the loan, while others only lock in the rate for a period of time. An adjustable rate mortgage (ARM), such as a 5-year or 7-year ARM, locks in the interest rate for 5 or 7 years. After that period, the interest rate adjusts to the market rate, which could be higher or lower. Some loans are based on the fair market value (FMV) of the home. For example, above a certain purchase price, the mortgage would be considered a jumbo loan, with a slightly higher interest rate than a conforming loan with a lower FMV.

The second characteristic demonstrated by the table is the concept of points. People pay points up front (at the beginning of the loan) to secure a lower interest rate when they take out a home loan. For example, potential borrowers might be informed by their loan officer that they could secure a 30-year loan at 5.0%, with no points or a 30-year loan at 4.75% by paying one point. A point is 1% of the amount of the loan. For example, one point on a $100,000 loan would be $1,000.

Whether or not buying down a lower interest rate by paying points is a smart financial move is beyond the scope of this course. However, when you take a real estate course or decide to buy and finance a home, you will want to conduct your own research on the function of points in a mortgage.

The third and final characteristic is that when you apply for and secure a home loan, there will typically be an assortment of other costs that you will pay, such as loan origination fees and a survey fee, for example. These additional costs are reflected in the loan’s annual percentage rate (or APR). These additional costs are considered part of the costs of the loan and explain why the APR rates in the table are higher than the interest rates listed for each loan.

(Figure) shows data from the Wells Fargo website. You will notice that there is a column for “Interest Rate” and a column for “APR.” Why does a 30-year loan have an interest rate of 4.375% with an APR of 4.435%? The difference results from compound interest.

Borrowing $100,000 for one year at 4.0%, with interest compounded yearly, would lead to $4,000 owed in interest. But since mortgages are compounded monthly, a mortgage of $100,000 would generate $4,073.70 in interest in a year.

Summary of Bond Principles

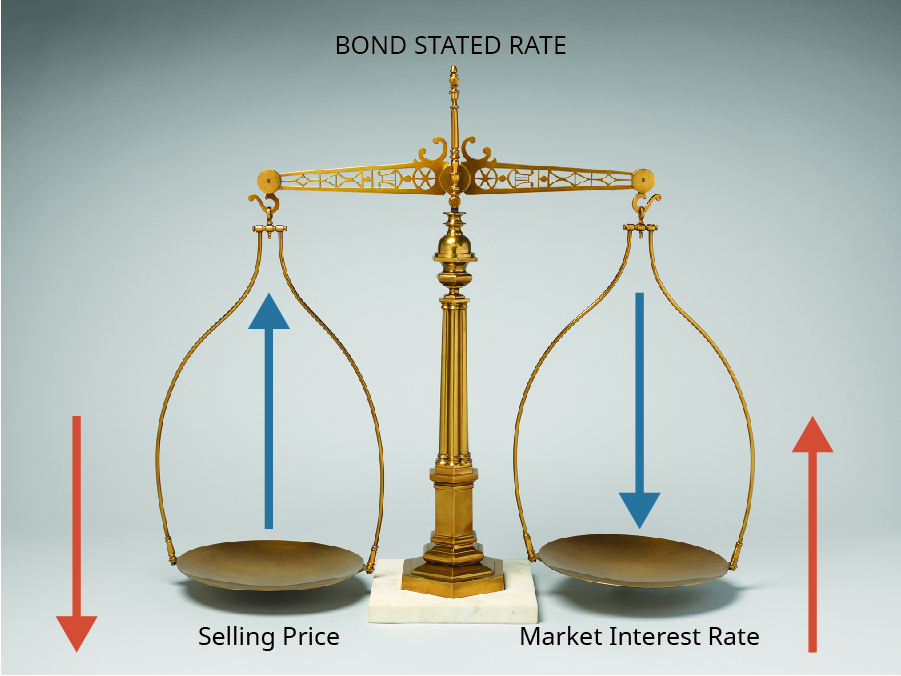

As we conclude our discussion of bonds, there are two principles that are worth noting. The first principle is there is an inverse relationship between the market rate of interest and the price of the bond. That is, when the market interest rate increases, the price of the bond decreases. This is due to the fact that the stated rate of the bond does not change.2 As we discussed, when the market interest rate is higher than the stated interest rate of the bond, the bond will sell at a discount to attract investors and to compensate for the interest rate earned between similar bonds. When, on the other hand, the market interest rate is lower than the stated interest rate, the bond will sell at a premium, which also compensates for the interest rate earned between similar bonds. It may be helpful to think of the inverse relationship between the market interest rate and the bond price in terms of analogies such as a teeter-totter in a park or a balance scale, as shown in (Figure).

In reality, the market interest rate will be above or below the stated interest rate and is rarely equal to the stated rate. The point of this illustration is to help demonstrate the inverse relationship between the market interest rate and the bond selling price.

A second principle relating to bonds involves the relationship of the bond carrying value relative to its face value. By reviewing the amortization tables for bonds sold at a discount and bonds sold at a premium it is clear that the carrying value of bonds will always move toward the face value of the bond. This occurs because interest expense (using the effective-interest method) is calculated using the bond carrying value, which changes each period.

For example, earlier we explored a 5-year, $100,000 bond that sold for $104,460. Return to the amortization table in (Figure) and notice the ending value on the bond is equal to the bond face value of $100,000 (ignoring the rounding difference). The same is true for bonds sold at a discount. In our example, the $100,000 bond sold at $91,800 and the carrying value in year five was $100,000. Understanding that the carrying value of bonds will always move toward the bond face value is one trick students can use to ensure the amortization table and related accounting are correct. If, on the maturity date, the bond carrying value does not equal the bond face value, something is incorrect.

Let’s summarize bond characteristics, When businesses borrow money from banks or other investors, the terms of the arrangement, which include the frequency of the periodic interest payments, the interest rate, and the maturity value, are specified in the bond indentures or loan documents. Recall, too, that when the bonds are issued, the bond indenture only specifies how much the borrower will repay the lender on the maturity date. The amount of money received by the business (borrower) during the issue is called the bond proceeds. The bond proceeds can be impacted by the market interest rate at the time the bonds are sold. Also, because of the lag time between preparing a bond issuance and selling the bonds, the market dynamics may cause the stated interest rate to change. Rarely, the market rate is equal to the stated rate when the bonds are sold, and the bond proceeds will equal the face value of the bonds. More commonly, the market rate is not equal to the stated rate. If the market rate is higher than the stated rate when the bonds are sold, the bonds will be sold at a discount. If the market rate is lower than the stated rate when the bonds are sold, the bonds will be sold at a premium. (Figure) illustrates this rule: that bond prices are inversely related to the market interest rate.

Footnotes

- 1 Nolo. “Financing a Small Business: Equity or Debt?” Forbes. January 5, 2007. https://www.forbes.com/2007/01/05/equity-debt-smallbusiness-ent-fin-cx_nl_0105nolofinancing.html#bd27de55819f

- 2 Another reason for the inverse relationship between the market interest rate and bond prices is due to the time value of money.

Glossary

- debt financing

- borrowing money that will be repaid on a specific date in the future in order to finance business operations

- equity financing

- selling part of the business to obtain money to finance business operations

Adapted from Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting (c) 2010 by Open Stax. The textbook content was produced by Open Stax and is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-financial-accounting

borrowing money that will be repaid on a specific date in the future in order to finance business operations

selling part of the business to obtain money to finance business operations